- 1920

- 1954

- 1979

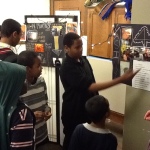

- Urban 4H Club

By Cassie Warholm-Wohlenhaus

This year the Franklin Library celebrates its 100th year serving a large area now called Phillips Community and Elliot Park, Whittier, Corcoran, and Powderhorn Park Neighborhoods. Exploring this history through research into the library”'s annual reports and other documents from 1914 to 2014 has revealed a fascinating and intimate bond between a community and its library.

2014 marks 100 years of service in the beautiful Carnegie library building at 1314 E. Franklin Avenue, but the library as an organization predates the building. It originally operated out of two rented rooms in the A.J. Bernier building at Franklin and 17th starting in 1890. In the library”'s earliest days this was a neighborhood largely of Scandinavian immigrants, and a huge collection of Swedish, Norwegian and Danish books and newspapers was in constant demand. An influx of Jewish immigrants in the 1920s added Yiddish and Hebrew to the languages heard at Franklin. The life of the library has reflected the community around it since the early days. The effects of world events and community unrest could also be seen””the neighborhood”'s men went off to fight in World War I and mothers kept their children home during Spanish flu and smallpox epidemics. The community needed information and entertainment during times of trial, and Franklin offered an important community space for that. Despite being a small branch library, Franklin often had the largest circulation numbers in the Minneapolis Public Library system.

The 1930s hit the surrounding areas hard, and the Great Depression”'s effects of high unemployment and extreme poverty crept into the library as well. Budget cuts, little money for books, and few open hours meant that Franklin”'s librarians struggled to serve the community. In these hard times, though, the neighborhood needed its library more than ever. With strong support from the community and a need for books, programs, and a free community space, the Minneapolis Public Library system agreed to expand the library building in 1937.

World War II brought with it many changes: loss of neighborhood men to military service, women working in large numbers outside the home in local factories, offices, and stores, extensive rationing, and a focus on international events and the war. Franklin Library supported the war effort by maintaining a collection of current books and newspapers on world issues, serving as a center for Red Cross work, and by being a community space where people could come together during this difficult time.Â

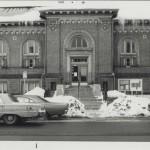

The 1950s began a push toward modernity in the library and the neighborhood: the building was converted from coal to oil heating and Franklin Avenue was widened and paved for the first time. Plans for the expansion of the University of Minnesota to the West Bank and construction of an East-West freeway (94) were underway. The neighborhood”'s makeup was also changing: Scandinavian immigration had begun its decline in the 1930s, and more African Americans and Native Americans were calling t Phillips and surrounding neighborhoods home than ever before.

The 1960s were a time of incredible neighborhood upheaval. Construction on highway 94 began in earnest in 1964, and was a painful process: extensive demolition of homes in the heart of the neighborhood, infrastructure changes, and freeway construction just 2 blocks north of the library forced many residents south or out of the area entirely. Powderhorn Community that included Phillips Neighborhood and seven other neighborhoods became a focus for federal and state housing projects to accommodate the displaced.

In response to all of this, the Franklin librarians recognized the need to rethink library service. They connected with organizations and non-profits and went out into the streets to meet people on their own home turf. This was also when the decision was made to relocate the Scandinavian collection to the central library, making space to establish Franklin”'s American Indian collection.

By 1970 a new freeway cut through the neighborhood, residents were moving from homes to housing projects, and crime was increasing. Throughout the decade the American Indian community responded passionately, spearheading efforts to lift the neighborhood out of this depression. Franklin Library created partnerships with these and other organizations in its efforts to get services and resources into the hands of community members. The library also established the experimental Neighborhood Information Center in 1974, which provided assistance around topics like housing, daycare, health, employment, legal assistance, alcoholism, and other topics. The library was renovated again in 1979 to increase capacity and remove physical barriers to disabled patrons.

In the 1980s condemned buildings were numerous, violent crime was on the rise, and residents moved out of the neighborhood in droves; in many ways, the hard luck story of the 60s and 70s continued. However, the community had already built a strong network of support organizations. Redevelopment projects took place along Franklin Avenue, residents established local businesses, and community spaces that celebrated the diversity and cultural identity of the neighborhood took shape. Franklin Library became one of several community anchors as the area rallied to rebuild and restore itself, providing library resources, meeting spaces, and the brand new Franklin Learning Center.

The library, as we know it today, really took shape in the 1990s. Technology was an important focus: the first computer circulation system was installed at Franklin in 1986, but it wasn”'t until the late 90s that there was access to the World Wide Web via a staff computer, then two public computers, and finally the Phillips Technology Center computer lab. The Homework Help program began with a U of M student as its sole tutor and was an instant success. The Franklin Learning Center”'s ESL, GED, and citizenship classes were full, and the library”'s basic education resources expanded to meet the needs of those patrons.

The American Indian section, the only collection of its kind in the library system, continued to expand and circulate, and the library was chosen to be the site of an Honor Village for its service to the Native community. By 1995 the largest single group using the library was Somali, and with a growing Hispanic population, Franklin responded again by expanding world language collections. Since then the Spanish, Arabic, Amharic, and Oromo collections have grown and the Somali collection became the largest of the local libraries.

In 2000 the Franklin Library building was added to the National Register of Historic Places, and was renovated in 2005 to improve technology resources in the building and preserve its historic facade. Even during the closure for renovation the library saw heavy use in an interim space next door. The grand reopening of the “new Franklin” was a joyous celebration of the renewal of this cherished place.

In 2008 the Minneapolis Public Library system merged with the county, and thus the Franklin Community Library became Hennepin County Library-Franklin, offering expanded services alongside the collections that had served the community for so many years. 2008 also saw the start of the Teen Center, designed by teens for teens. They claimed the space as their own, building leadership and community stewardship, and seeing their ideas and passions come to life.

This year Franklin Library is proud to celebrate 100 years of service. In the last century it has weathered wars, epidemics and depressions; neighborhood upheaval and dramatic change; times of hard luck and rebirth. Most importantly, the library has grown with the community through both the good and bad. It is a place that reflects the hope and vitality of the indomitable Phillips Community and will continue to do so for many years to come.

Cassie Warholm-Wohlenhaus is a Librarian at the Franklin Library. She was featured in an aricle by Erin Thomasson in the October issue of The Alley Newspaper.