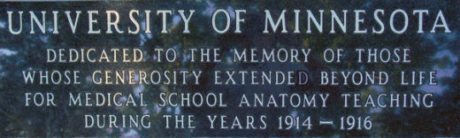

A simple tombstone of austere black granite at the extreme northeast corner of Pioneers and Soldiers Cemetery marks the “Potter”'s Field” resting place of 350 people. This marker of reparation cannot identify and give proper acknowledgement of each life, but it does bear witness that a large institution can acknowledge and begin to repair a previous injustice delivered by those in decision-making roles at that time.

On September 9, 2012, there will be a dedication and remembrance ceremony for 350 people whose deaths passed more or less unnoticed in the early part of the 20th century. They are buried together at the bottom of the hill in the Potters Field at Minneapolis Pioneers and Soldiers Memorial Cemetery. As Francis Phelan, protagonist of William Kennedy”'s Ironweed, viewed it, they are neighbors, situated in this particular place since some time between 1914 and 1916. They are the people whose remains were the subject of study at the University”'s anatomy program during those years. The contributions that they made to medical research will be acknowledged when a black granite marker, a gift from the University of Minnesota, is dedicated to their memory on Sunday, September 9th.

Who are the people being honored? One hundred of them are infants who were stillborn or who died shortly after birth in one of the city”'s charity hospitals. Most of the rest were adult men who ranged in age from 21 to 80 years old. Many of them were immigrants, most from Scandinavia but from countries like Poland, Ireland and Macedonia as well. They tended to be unskilled migratory workers who came to the city from mining and lumber camps up north or from the harvest fields in rural Minnesota and the Dakotas. They were men who were willing and able to work in isolated areas as long as there was work to be done. When the work ran out or when winter set in, they headed back to the city and tried their best, though not always successfully, to fit in.

They died from any number of causes. Heart disease, cancer and tuberculosis (known as the “white plague”) were the leading causes of “natural” deaths. Accidental deaths were common, especially accidents that occurred in the railroad yards. Deaths due to “falls” were not uncommon. And, of course, alcohol was often a factor in accidental deaths.

Many of the men died in charity hospitals, and although hospital administrators and the county coroner attempted to locate relatives, they were often unsuccessful. It was easy for men to get lost back in the days when there were no drivers”' licenses, no social security numbers, no standard forms of identification. The newspapers were full of stories about families trying to locate missing relatives, wanting them to come home. Many families waited in vain for word from their missing husbands and sons. Nineteen of the men are identified only as “unknown man.” Several others are elderly widowers who had no wives or children left to arrange for their burials. Regardless of who they were or where they came from, their remains were buried without fanfare or mourners at the end of each academic year. This year, thanks to the University of Minnesota, they will receive the acknowledgment that they deserve.

The dedication and remembrance ceremony will begin at 1:30. Following the ceremony, light refreshments will be served and guests will have the opportunity to learn more about the history of medical research in the early 20th century and about the people whose lives are being remembered. Please join us on this very special occasion. Everyone is welcome.