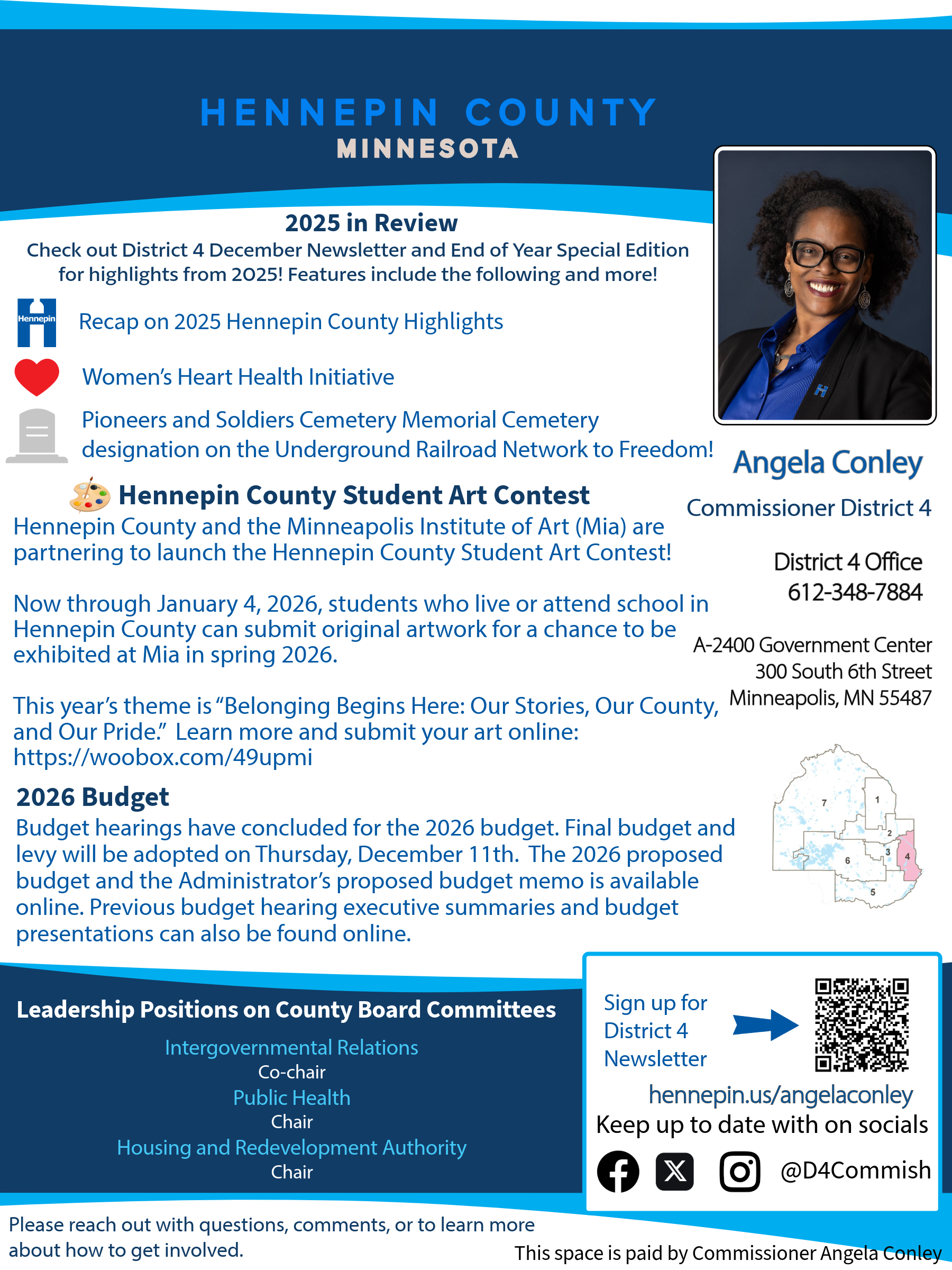

Minneapolis City Hall and Hennepin County Courthouse (also known as the “Municipal Building”), designed by Long and Kees in 1888, is the main building used by the city government of Minneapolis, Minnesota as well as by Hennepin County, Minnesota. The structure has served many different purposes since it was built, although today the building is 60 percent occupied by the city and 40 percent occupied by the County. The building is jointly owned by the city and county divided right down the middle and controlled by the Municipal Building Commission. This photo is from the early 1900”'s showing that little has changed with the building”'s exterior while the surroundings have changed greatly.

By Sue Hunter Weir

119th in a Series

2014 almost 4x more per capita and guns used over twice as often

Minneapolis closed out 2014 with 32 murders of record*. The number is low in contrast to many other recent years but it is still much higher than the murder rate of 100 or so years ago. In 1912, there were ten murders in Minneapolis””four of the victims are buried in Pioneers and Soldiers Memorial Cemetery. Four of those ten murders, including two of the people buried in Pioneers and Soldiers, were never solved.

There was nothing particularly clever about how any of the murders were committed. Only one of the ten deaths was planned in advance, and even then the murderer made a terrible mistake. On February 10th, someone left poisoned candy on the doorstep of Simon O”'Malley, the intended target. Unfortunately, O”'Malley gave a piece to his three-year-old-neighbor, Bonnie Ready, and she died as well, a child in the wrong place at the wrong time. Their murders were never solved.

The four people buried in the cemetery are Alice Mathews, Fred Wescott, William Burke and Henry Carlson. Alice”'s case, like Simon O”'Malley”'s, demonstrates how little police knew about forensics at the time. Police did some fingerprinting and chemists could analyze and identify certain toxic substances but that was about the limit of the science available to help police solve crimes. Even when they were convinced they knew who the murderer was, they were often unable to prove it. They were forced to rely on eyewitnesses and on confessions, neither of which proved to be particularly reliable.

Alice Mathews was strangled during a failed rape attempt on March 23, 1912. There were no obvious suspects although the police, who were under intense public and political pressure to solve the case, arrested at least half-a-dozen people and held them for varying lengths of time before concluding that they had no case against any of them. Over the next several years, one man, with a lengthy history of mental illness, repeatedly confessed to Alice”'s murder. Police listened to him each time even though they knew that he couldn”'t possibly have committed the murder. This self-confessed “killer” was determined to convince them otherwise but never succeeded.

Police believed that Fred Wescott was stabbed by Isabel Getzman, better known by her stage name, “Scotch Maggie.” A witness had seen the two arguing in the back of the Rising Sun Café, which Getzman owned and where Wescott was employed as a cook. The police arrested Getzman but their case against her fell apart when their only witness disappeared.

The other two burials were for William Burke and Henry Carlson, both of whom died from skull fractures. Burke fought with a patron of the Cedar Avenue Saloon where both had been drinking. He was arrested and sentenced to five days in the workhouse, but he was sick and unable to work during his stay there. Two days after he was released his wife took him to the hospital where he died from an injury that he had received the night that he was arrested almost two weeks earlier.

Carlson died from a blow that he received from David Ploof. The two men had been at a party when they started to argue. Carlson used “vile language” about Ploof”'s wife. The two men encountered each other in the street the next day and the fight continued. Ploof struck Carlson who fell and hit his head. Carlson made it home under his own power but died a few hours later.

Three of the ten murders committed in 1912 involved guns. Two of those cases were domestic homicides””husbands killing their wives. In both cases, the women had left their husbands. The third case was a shooting at a party where a man was killed because he refused to hand over the ten cents that he owed to the man who killed him.

Guns were involved in 30% of the murders in 1912. At the time there were 300,000 people living in Minneapolis, and it was the country”'s 18th largest city. Today the city”'s population is 400,000 (a 25% increase). If the murder rate had increased at the same rate as the population there would have been between 12 and 13 murders in 2010. Instead there were 40, 30 of which (75%) involved guns.

Alice Mathews, Fred Wescott, William Burke and Henry Carlson are buried in unmarked graves in various locations throughout the cemetery.

*Subject to changes; e.g. a delayed death.