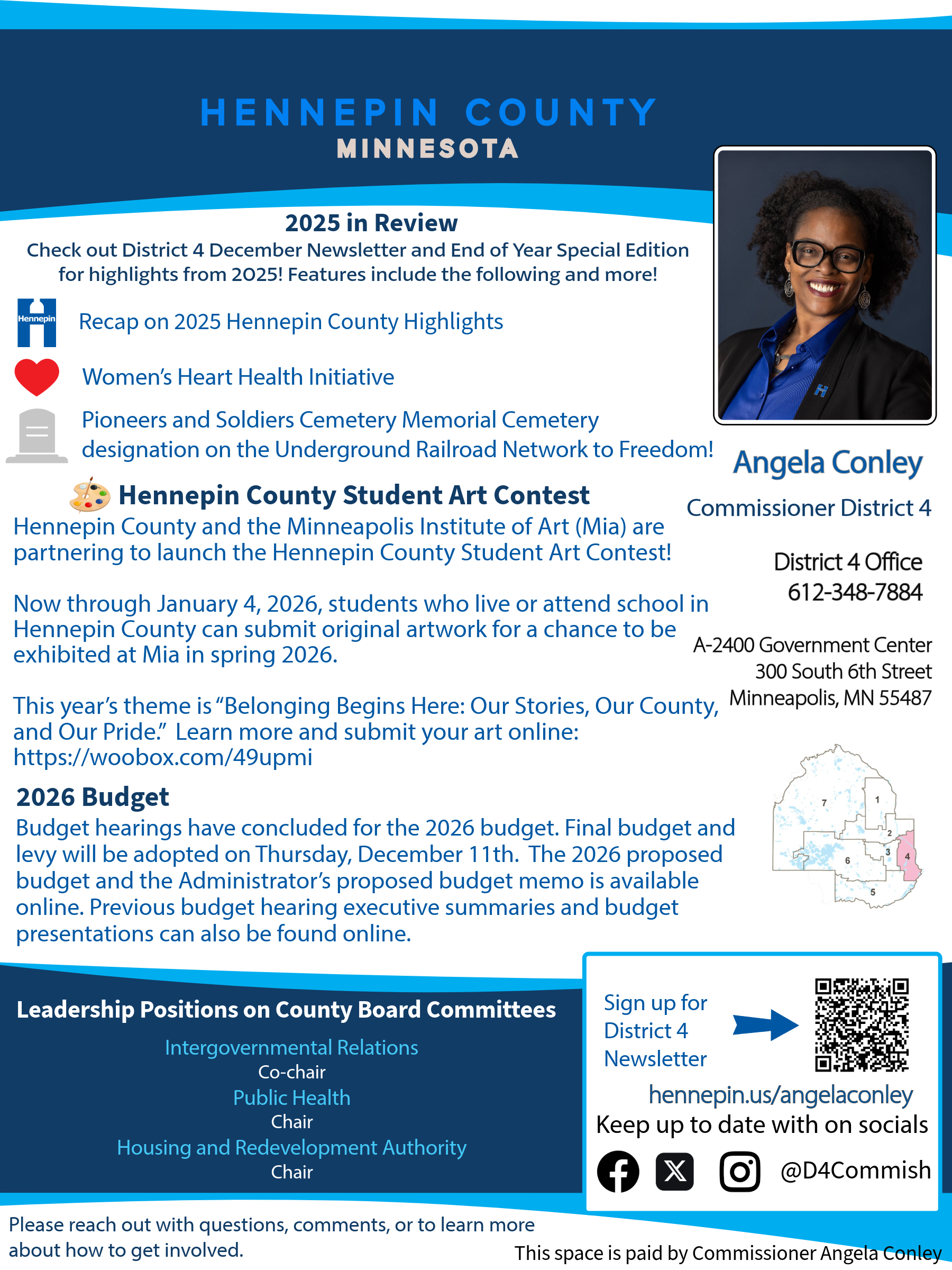

This future leader will be able to walk through the English curtain at will and leave it all behind having learned Objibwe and/or Dakota culture, traditions, and language; and the wholeness of the circle of life. He will understand how important autumn is”¦the timing of the leaves that turn to color ”“ bronze, yellow, orange, red ”“ signal when they choke off the flow of nutrients to their leaves whether winter will be early or late. Photo: Jewell Arcoren

BY LAURA WATERMAN WITTSTOCK

Before cars, before buildings, before the incessant consumption of natural resources, there was another population that went through the seasons, adjusted to disasters, fell in battle, and buried their dead.

In less than 100 years, European settlers managed to wipe out over 90% of the old growth forest in what is now Minnesota. Before the arrival of the French and the Ojibwe, the river along what is now St. Paul, bustled with the canoe and watercraft traffic of the Dakota people and their Hidatsa allies. The canoes, heavy with rice and other grains, headed down the river to what is now St. Louis where a huge trading center was supported by the exchange of goods and services of many tribes. They came back with medicines, new foods, and robes for the winter to add to what they already tanned.

It was labor intensive and women were at the forefront of the trading. The men hunted and defended the villages of the people. In 1834 the missionaries Samuel W. and Gideon H. Pond with Stephen R. Riggers and Thomas S. Williamson put together a Christian version of written Dakota. The resulting dictionary, still in print, has such words as pickle, picnic, pictorial, picture frame, and physics. This was far from the reality of the Dakota people, who came from the stars and understood every plant and tree, every change of season, and every animal in their territory. The printed words stunted their knowledge generation after generation until it seemed they might disappear.

But they did not disappear. The Dakota language, rich and full of meaning and nuance, moved beyond the curtain of English that was papered everywhere in writing and talk. If you know the Dakota language, you can walk through that English curtain at will and leave it all behind. You understand how important autumn is ”“ not just a time to think about buying a sweater.

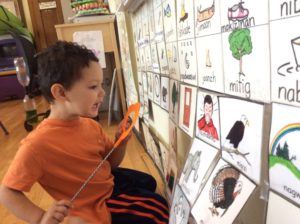

Leaves tell their story. Now, little children walk from their Dakota and Ojibwe classes in the Phillips Neighborhood with their teacher to a nearby garden. He points out the various plants and trees along the way and says their names. The children learn as another season turns in their young lives. There will have to be many more seasons in their Dakota and Ojibwe classes before they are self-assured and can easily transgress the English curtain into the Dakota and Ojibwe language and cultural world. Photo: Jewell Arcoren

The timing of the leaves that turn to color ”“ bronze, yellow, orange, red ”“ signal when they choke off the flow of nutrients to their leaves whether winter will be early or late. It is interesting to look at trees, to understand one kind from another and to know the uses of the trees. Sugar maples that once filled the hardwood forests are now seen in tiny stands. The Dakota people made maple products for energy-rich food that could be consumed the whole year.

But now, the leaves tell their story. Now, little children walk from their Dakota class in the Phillips Neighborhood with their teacher to a nearby garden. He points out the various plants and trees along the way and says their names. The children learn as another season turns in their young lives. There will have to be many more seasons in their Dakota classes before they are self-assured and can easily transgress the English curtain into the Dakota language and cultural world.

Laura Waterman Wittstock is described on Page 9 of this October issue of The Alley Newspaper where it also explains how you may hear her on First Person Radio KFAI 90.3 FM ”“ Mpls. 107.6 FM St. Paul Wednesdays 1:00-2:00 PM.