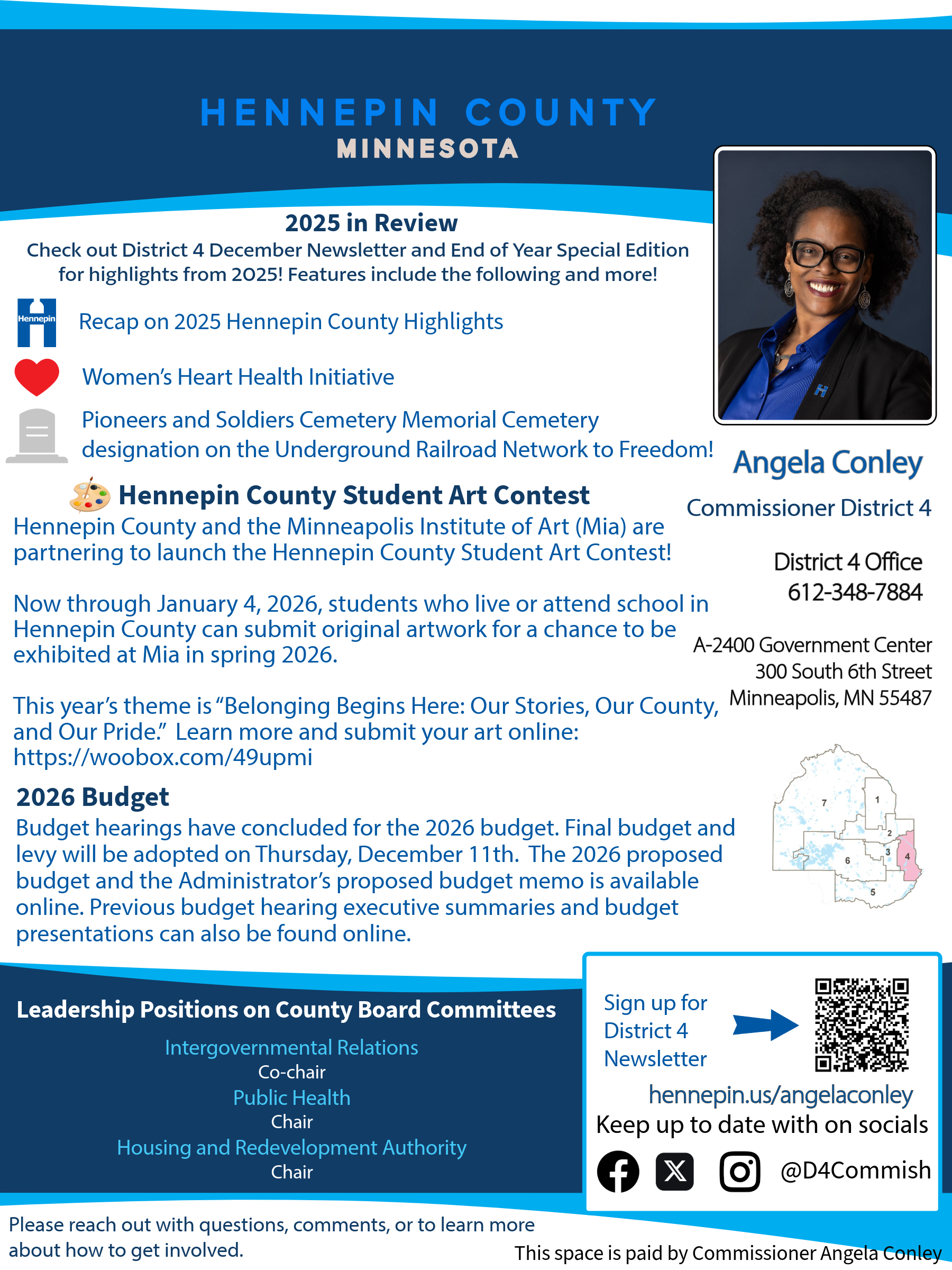

COURTESY MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY | The fence in the background is the fence surrounding the old trolley barns on 21st and Lake. Notice the dirt roads for maintenance carts and, in their day, the old horse-drawn hearses.

After 7,000 bodies were exhumed and moved from disheveled cemetery

By SUE HUNTER WEIR

154th in a Series

In April 1919, the Minneapolis City Council voted to close Layman”'s Cemetery to future burials. What followed was the most chaotic period in the cemetery”'s history. It was a time when tall tales and extravagant claims were picked up and repeated in the newspapers. It was a time when the editorial pages of the local newspapers published dozens of letters from citizens arguing in favor of protecting the cemetery and from those who argued that the land should be cleared for commercial development or for recreational uses.

There is little doubt that the cemetery had fallen on hard times and that local business owners and homeowners had cause to be concerned. Markers had fallen over, weeds and grass were knee deep; there was no fence so the cemetery was open to trespass.

The Layman Land Company, descendants of the cemetery”'s original owners, offered to disinter the bodies of those whose families wished to have them moved and, under certain conditions, to pay for new “boxes.” The cemetery”'s superintendent reported that 40% of the lots had been cleared, but he only counted lots with multiple graves and not the many thousands of single graves. (Current estimates are that approximately 7,000 people were removed, and slightly fewer than 22,000 remain so the percentage of removals is closer to 24% than 40% as reported.)

Initially, arguments about who was responsible for having let the cemetery wind up in such a sorry state resulted in a lot of finger pointing but little action. Members of the Minneapolis Cemetery Protection Association, a preservation group founded in 1925, argued that cemetery maintenance was the responsibility of the Layman Land Company and proposed taking legal action to force them to maintain the cemetery properly. Martin G. Layman, the cemetery”'s superintendent and the grandson of Martin & Elizabeth Layman, the cemetery”'s original owners, rightly pointed out that his relatives had made no provision for perpetual care of the graves other than charging an $1 or $2 annual maintenance fee. He said that in 1924 only seven families had paid the fee which may have been the result of confusion about what the city council”'s action in 1919 meant; the distinction between the cemetery”'s being closed versus it”'s having been condemned (which would have required the removal of bodies) was one that many people did not understand and was further muddied by Mr. Layman”'s claim that no one knew what the future held for the cemetery.

In 1925, the state legislature passed the Enabling Act which would have given title to a 175-foot-wide strip along Lake Street to the Layman Land Company, and which would have given the Minneapolis Park Board the authority to condemn the cemetery. Once condemned, the Park Board would own, at no cost, all of the land except the 175-foot-wide strip fronting Lake Street. Oddly enough, no one had asked the Park Board whether they wanted additional land and it turned out that they did not.

COURTESY OF THE MINNESOTA STREETCAR MUSEUM | In background about 1947, P & S Memorial Cemetery”'s eastward proximity to the Twin City Rapid Transit Co. streetcar storage and maintenance yard impacted it”'s aesthetic and vulnerability to future development as the imminent demise of streetcars preceded its final transition to buses by decades. Exceptionally large (compared to other cities) TCRT streetcars were built at the Yard at Nicollet and Lake St. History reveals a frequent relationship between street car transit, amusement parks, and ball parks; e.g. the area north of the Nicollet Yard became Nicollet Baseball Stadium, MN United Soccer $150 M stadium currently being built on the former Snelling Streetcar Yard, conversion to more mobile, rubber-tired buses ”“ led to personal profiteering during the transition as officials were stripping TCRT of its assets to fill the pockets of owners and investors. Major owner, Fred Ossanna, was convicted in 1960 of illegally taking personal profit from the company during the transition period. He was imprisoned along with other accomplices. Carl Pohlad, who became the owner of the Minnesota Twins in 1984, was the eventual successor of Ossanna as head of Twin City Lines in the 1960s. He ultimately sold the company in 1970. Architecturally renderings of a new shopping center indicate the incentive for Layman descendants to exhume approximately 7,000 bodies.

The proposal to convert part of the cemetery into a park came after several other ideas had been proposed (or at least rumored) but failed to materialize. Among them were a new Milwaukee Road Railroad Depot, a proposal for the Ford automotive plant, a market, an auditorium, and a tourist camp. Of all of the proposals, the park proposal sparked the greatest controversy. It pitted those who insisted that the city”'s Founding Fathers would not have wanted children to be deprived of their right for a place to play against those who argued that the cemetery was sacred ground and that the removal of the cemetery was disrespectful and an act of desecration.

Politicians who introduced the Enabling Act or supported its passage had seriously underestimated the fury and political power of the descendants of those buried in the cemetery. Many of the “Pioneers”' Children,” as one paper named them, stood ready to take the battle to court. They were joined in their struggle by a variety of veterans groups, the Odd Fellows, Territorial Pioneers, and Boy Scouts. Hundreds of interested people attended meetings of the Minneapolis Cemetery Protective Association.

In 1927, under significant political pressure, the Minnesota Legislature rescinded the Enabling Act and approved a request for the city to sell $50,000 in bonds. Of that, $35,000 was used to buy out the Layman heirs and the remaining money was used for improvements to the cemetery grounds. The city assumed responsibility for maintaining the cemetery”'s structures and grounds but families of those who were not moved retained ownership of their graves.

The cemetery was recognized as a memorial to the veterans and city”'s early residents and was renamed Minneapolis Pioneers and Soldiers Memorial Cemetery with emphasis on the word “Memorial.”