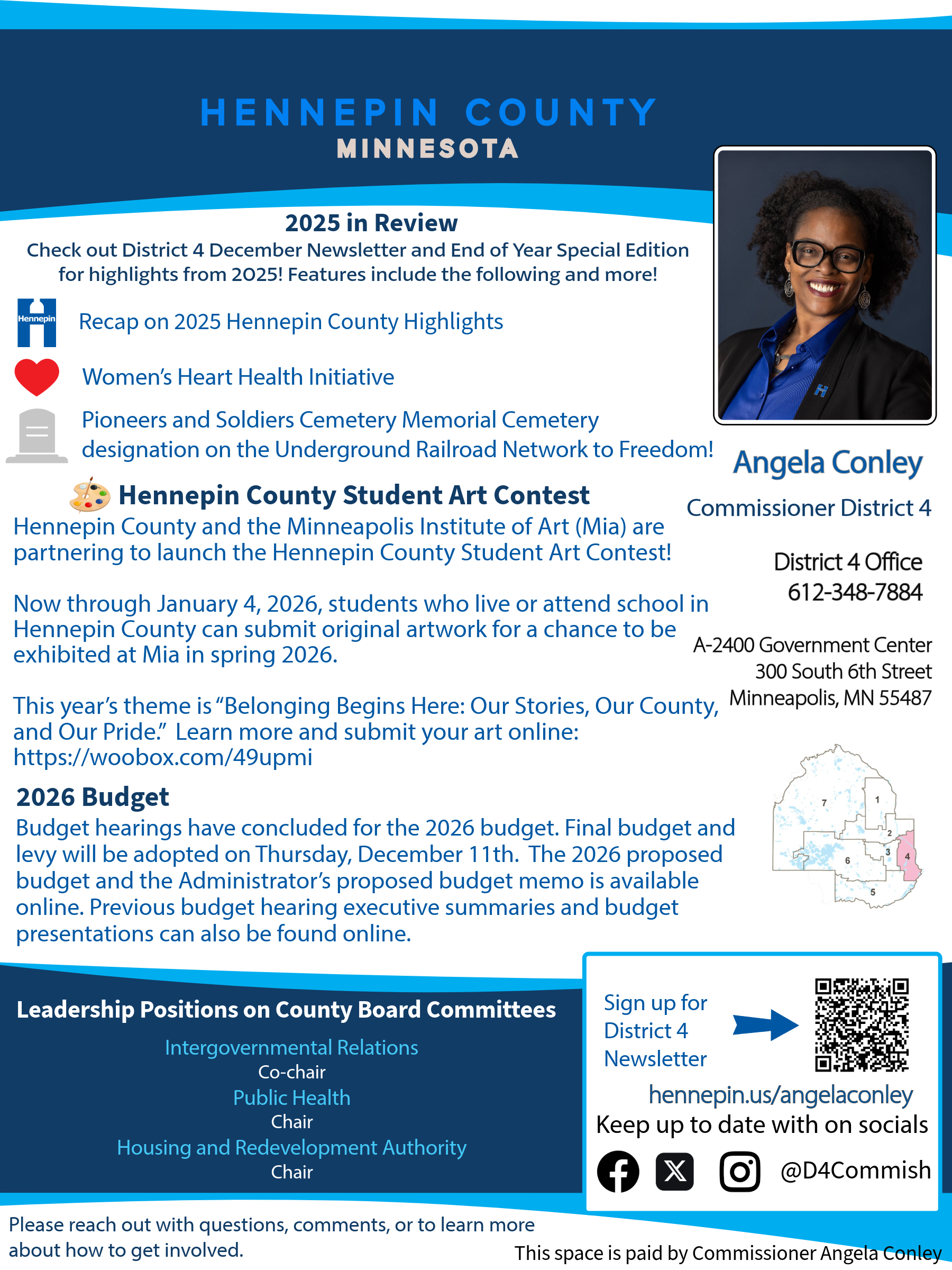

DICK BANCROFT

These men photographed and documented by Dick Bancroft are a few of the many representatives attending the 1977 UN Geneva Conference. Left to right Ted Means, Greg Zephier, Russell Means, Oren R. Lyons, Jr., Larry Red Shirt, and Francis Andrew He Crow

First Declaration of International Indigenous Day

By LAURA WATERMAN WITTSTOCK

In the August issue of The Alley, I told readers the story of how Dick Bancroft loved cameras and picture taking since he was a young boy. Dick died at the age of 91 on July 16th. What I did not fully explain is that he spent years on his collection of photographs, much of it with Jaime Haire, his editor and archivist. Jaime worked diligently on the photographs that appeared in Dick”'s book, We Are Still Here, published by the Minnesota Historical Society Press in 2013. Dick and I collaborated on the text and photos with pretty much him doing the photos and me doing the text. His photos are brilliant and clearly illustrative of the period 1970 to 1981 when the American Indian Movement was most active or influential.

Here are just a few of the photographs and quotes from the book so you can hear what Dick and I heard from the participants as they reflected on the times and events. The focus here is on the Geneva Conference of 1977.

In preparing for the book Dick said, “I wasn”'t apprised of what occurred two years prior to that when the treaty council was formed in Wakpala. I didn”'t know about that ”“ I missed it. Why, I don”'t know. But, in 1977, I was tipped off by the fact that they were going to go to Geneva. I said, “Who”'s going to Geneva?” and they said, ”˜The Treaty Council,”' and so I said, ”˜What”'s the treaty council?”' Pat [Bellanger] and others would tell me about it. I was going to be on that trip.”

Dick had a lot of changes to make with his cameras to prepare for the trip. He told me “In those days, I didn”'t use zoom lenses but I do now and so I had to change lenses from a 35mm to a 80mm and you had to click them off and on. It was a lot of work. I carried four lenses and two cameras: two telephotos lenses and a 50mm and a 35mm wide angle.”

DICK BANCROFT

Ted Means, Pat Bellanger, and Bill Wahpepah standing at the podium where speeches and over a hundred testimonies of abuse and exploitation were given at the 1977 UN Geneva Conference.

Dick said, “This was big time. By this time I was using two cameras. I lost my Leicaflex in the fire [his house burned down] and I had two Cannon 35mm cameras. I used those cameras in Geneva.”

In the book Dick says, “After Wakpala, it was logical that I go to Geneva. I have to say, that one of the things that occurs when you”'re working with a camera like this is feeling an adrenaline rush. To be able to walk into the United Nations building, the Palais des Nacions, with a camera around my neck and have the drum and these people coming in wearing full Indian regalia was stunning. This was frowned on by the United Nations. They didn”'t want people to be in traditional dress; they wanted people to be in suits and ties. Well, the American Indian Movement said, ”˜No way, we”'re coming in the way we want to dress.”'”

The photographs with this article show the excitement Dick felt as he squeezed off shots. For him, it was a world of difference from suits and ties and the quiet determination he had witnessed in his father”'s business conference rooms.

Dick told me, “Personal needs are put in the background. As a result, it was exhausting. I met Winona LaDuke for the first time and she gave a significant statement at the UN. I met Bill Wapapah for the first time and Oren Lyons. Philip Deere was prominent in Geneva””he had stayed at our house during the Wounded Knee trials. He was from Oklahoma, and he had a technique for selecting prospective jurors. He would tell Ken Tilson or the other lawyers””don”'t take this one or use your objection and get rid of this one. He would sit there in the courtroom during the jury selection and then he would spend the night with us.”

DICK BANCROFT

Ted Means, Pat Bellanger, and Bill Wahpepah standing at the podium where speeches and over a hundred testimonies of abuse and exploitation were given at the 1977 UN Geneva Conference.

Years later, I met Winona LaDuke in a noisy hotel room as she was taking her grandchildren for a holiday visit to a waterpark near Minneapolis. When asked about Jimmie Durham, who organized the conference, La Duke said, “I was a young woman at Harvard in 1976 and I remember hearing this man talk to our school. His name was Jimmie Durham and he represented the International Indian Treaty Council. It was the first NGO at the UN that represented Indigenous people. They had a presentation by him and I thought, ”˜Well that is really right what he said.”' It changed my world view. “

Between taking care of her tykes and answering phone calls, the busy organizer reflected on being 18 again, learning to research deeply. She had research experience but this was different. She had never been to the Dakotas. LaDuke talked about how impressed with the elders she was and how clear-spoken Lakotas and Dakotas were when they rose to lay out plans. She listened to Lorilei Means and Madonna Thunderhawk.

Dozens of others from all over the hemisphere worked on the “Declaration of Principles for the Defense of the Indigenous Nations and Peoples of the Western Hemisphere,” which was drafted on September 23, 1977 and affirmed by ten resolutions. The final version, The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was adopted by the General Assembly on Thursday, 13 September 2007 with many changes on “Thursday, 13 September 2007, by a majority of 144 states in favour. “

Dick placed this quote by Tatanka Iotanka at the beginning of the book: “I am a red man. If the Great Spirit had desired me to be a white man he would have made me so in the first place. He put in your heart certain wishes and plans, in my heart he put other and different desires. Each man is good in his sight. It is not necessary for Eagles to be Crows. We are poor”¦ but we are free. No white man controls our footsteps. If we must die”¦ we die defending our rights.”

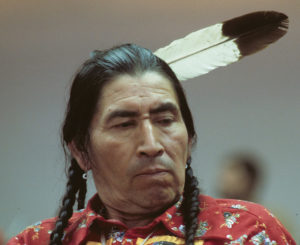

DICK BANCROFT

Phillip Deere – Muscogee (Creek) 1929 – 1985. An inspiring traditional Muscogee (Creek) healer from Nuyaka Grounds, Okemah, Oklahoma, who became a spiritual leader, civil and human rights activist, oral historian and storyteller; a founder of the Traditional Youths and Elders Circle and a spiritual guide for the American Indian Movement (AIM). He was an elder and statesman for the International Indian Treaty Council (IITC), and participated in the United Nations International Human Rights Commission held in Geneva, Switzerland. He spoke about remembering traditional values, Muscogee prophecies, care for Mother Earth, and brought attention to injustices suffered by indigenous peoples of the Americas. He said, “No more are we going to stand around ”¦ This is not the end of The Longest Walk!”

October 8th: International Day of Solidarity with Indigenous Peoples of the Americas

Why was the September 20-23, 1977 UN Geneva Conference so important?

The United Nations, for the first time, formally recognized Indigenous Peoples of the world by granting the International Indian Treaty Council, the political arm of American Indian Movement, Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) status.

The International NGO Conferences on Discrimination Against Indigenous Populations in the Americas, held at the United Nations”' offices in Geneva on September 20-23, 1977, was a watershed event, the very first UN conference with Indigenous delegates, the first direct entry of Native peoples into international affairs, the first time that Native people were able to speak for themselves at the UN. Some governments felt so threatened that they prevented delegates from participating and persecuted them upon return.

Following a Lakota pipe ceremony and opening presentations, Russell Means made the keynote speech, followed by more than a hundred Native representatives detailing systematic abuses of their human rights and the expropriation and destruction of their lands and natural resources by governments and corporations. In the end, the conference produced the first draft of what eventually became the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (thirty years later in 2007) and resolved to observe October 12, the day of so-called “discovery”' of America, as an International Day of Solidarity with the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas.”

The event was the product of many hands and minds. One key person who brought it about, but did not actually attend, was Jimmy Durham, Cherokee artist-poet, first director of the International Treaty Council (IITC). According to Roxanne Dunlap-Ortiz, who was an IITC delegate at the conference, Durham played a pivotal role.