Mary Briggs, dies after 21 days of life

Mary Briggs was only 21 days old when she died from diphtheria on February 13, 1916. As tiny as she was, her death had long-lasting consequences for the City of Minneapolis, especially for babies born to mothers living in poverty.

Mary died at 3614 Grand Avenue in what was known as a “baby farm,” a privately owned boardinghouse for unmarried women and their babies. In addition to providing homes for “erring mothers” and “incorrigible girls” who were waiting to give birth, some baby farms served as adoption agencies. One woman advertised her business as a “private home for ladies before and through confinement.” She also advertised babies who were available for adoption””“Two pretty baby girls and a boy.” A few farms cared for children whose parents (usually mothers) had no one to care for their child while they worked.

The city had a number of ordinances that were intended to ensure the quality of care that the babies received but provided little in the way of resources, so inspections were rare and enforcement of existing laws was virtually nonexistent.

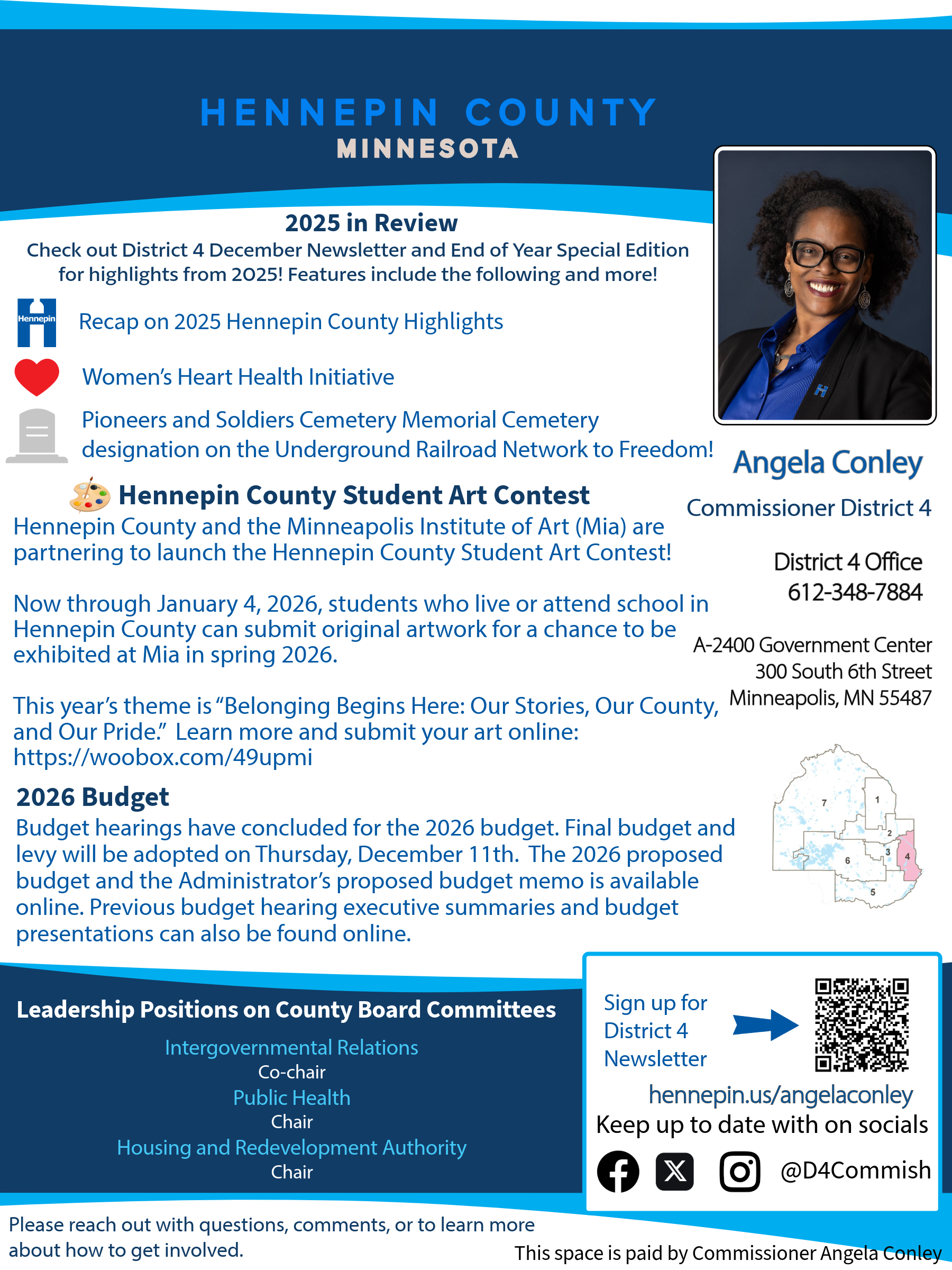

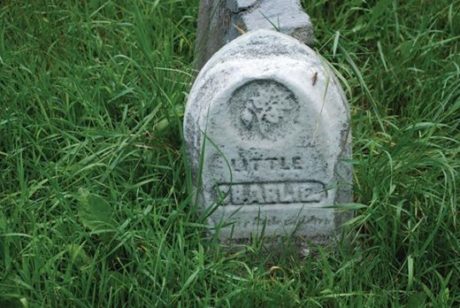

75+ Baby Farm babies buried at Lake & Cedar Cemetery

Mary was one of more than 75 babies buried in the cemetery who died at addresses that were known to be baby farms. The first that we can identify from cemetery records was May Coffin who died on February 26, 1895, more than 20 years before Mary Briggs. And May was only one of 31 children who died at the baby farm located at 1432 5th Street Northeast. The owner was Hannah Lund who was well known to police and social services in Minneapolis but who nevertheless managed to stay in business. No matter how appalling the care provided by the baby farms, the need for the services that they provided was great, especially by young women with little money and nowhere else to go.

Mary”™s death is catalyst for modest reform

Two days after Mary”™s death, the Humane Society (the city”™s department of social services) announced that Miss Caroline Forster, one of their staff, was being assigned to the City Health Department to monitor the conditions in what the city estimated to be 20 baby farms. Each newly admitted or recently born child would need to be registered and given a physical. Adoptions and transfers had to be recorded. Although inspections were rare, owners sometimes got word that an inspector was on his way and this comprehensive system of record keeping was intended to prevent the owners of baby farms from shifting babies around “whenever trouble [seemed] to be in the air.”

“The need would not go away!”

Miss Forster absolved everyone involved in Mary”™s care with any responsibility for her death. The Health Department, City Hospital officials, and Miss Kaufmann, the proprietor of the baby farm, were not to be blamed. Miss Forster said: “As baby farms go, Miss Kaufmann”™s place is as good as the rest.” She admitted, however, that Kaufmann”™s business should not have been granted a license because “”¦it is not adequately equipped to cope with such an emergency as the one now existing.” Forster added that it was unlikely that any of the baby farms in the city were adequately prepared to take care of seriously ill children but that if the city pulled all of their licenses, “wildcat farms,” operating under even worse conditions, would open for business. The need would not go away.

Change did not occur immediately following Mary”™s death but before the year was out 300 babies were being cared for in 13 licensed facilities. There were seven private maternity hospitals, where women could receive pre- and postnatal care, that were subject to the same regulations as other hospitals. The Humane Society opened a new department, the Children”™s Protection Society, which focused specifically on the needs of the city”™s children. In the month of November 1916 the department”™s staff made 30 inspections.

Although Miss Kaufmann was initially absolved of any responsibility for Mary”™s death, it wasn”™t long before Miss Kaufmann”™s name was in the news again. On May 10th, Kaufmann was denied a license to operate a second baby farm at 3108 17th Avenue South, an address where seven infants had died earlier. The reason given for denying Kaufmann”™s license was her careless handling of a number of diphtheria cases at 3614 Grand. One of those cases was baby Mary Briggs.

TIM MCCALL

TIM MCCALL

TIM MCCALL