By HOWARD MCQUITTER II

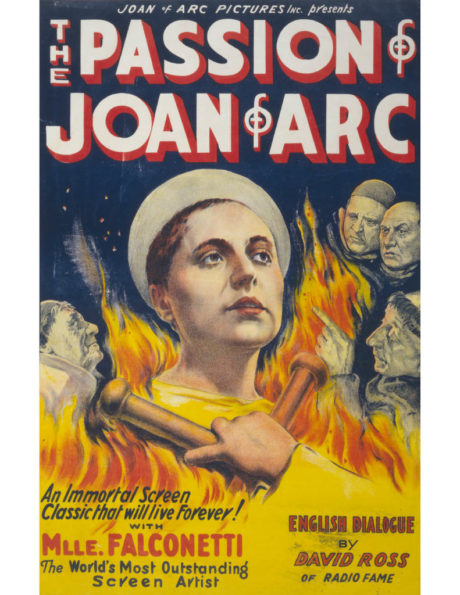

The best films are not necessarily current box office hits. Just the other day, TCM (Turner Classic Movies) featured one of the best films in film history which is The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). Directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer (Master of the House, 1925), the film showcases one of the most remarkable single performances by an actor in film history – Renée Jeanne Falconetti as Joan of Arc. She was known at the time for comedy routines in theater and cinema. What silent film thespians learn to master is visual expressions and body movements. In numerous closeups Falconetti does an amazing performance as the tortured Joan of Arc who is being accused of heresy by powerful ecclesiastical men. She does this for 110 minutes. It’s nothing less than extraordinary.

I saw The Passion of Joan of Arc many years ago, but after seeing it again recently I realized even more than before how great her performance is, as well as the film. Adding to the exceptional work is the director Carl Theodor Dreyer (1889-1968), born in Copenhagen, Denmark. He is considered one of the best directors and screenwriters of all time.

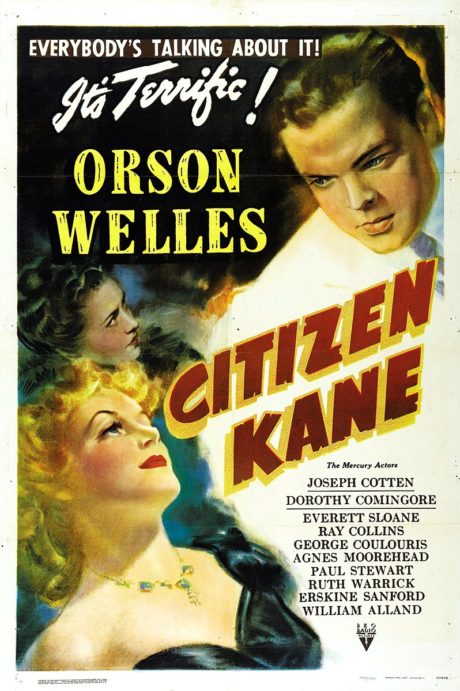

Many – if not most – film critics (at the present time) agree Citizen Kane (1941) is the best film ever made. A masterpiece without doubt, the film is complicated, mysterious and dramatic to its core. I saw it many years ago when I was much younger without grasping its contribution to cinema. Over time, watching Orson Welles in Citizen Kane (and in his large body of work directing or acting in his movies), I began to see why it is so revered by many film directors, screenwriters, critics and audience members. (The Third Man, 1949, is one of my favorite films of all time, with Orson Welles as principal actor along with Joseph Cotten and Alida Valli, directed by Carol Reed.)

Kane (Orson Welles) grows up in poverty and loves his sled, known as “Rosebud”, a term periodically used throughout the film. One day he is taken from his home and eventually amasses great wealth as a newspaper tycoon. Welles directed, produced, co-wrote (with Herman Mankiewicz) Citizen Kane. RKO Pictures was behind the film. But Welles’ Kane will soon become controversial because Kane parallels the contemporary William Randolph Hearst, the media mogul of the day. Hearst didn’t ignore the comparison to him and the term “Rosebud” which he interpreted as a reference to his mistress, Hollywood actress Marion Davies. Hearst refused to publish Kane in any of his newspapers and went further attempting to buy up the prints and destroy them. Hearst’s move also intended to destroy Welles’ career. Even though Citizen Kane garners several Academy nominations, it never wins best picture. At the 1941 Academy Awards, Citizen Kane won only best screenplay. Indeed, the influence of Hearst’s wrath made an impact.

In the film, Kane becomes a victim of his own success. Avarice, adultery, and cruelty gets the best of the man. What’s truly missing from his life is happiness. He divorces his first wife, Emily Norton Kane (Ruth Warrick) for a young dancer Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore). When warned by his manager Mr. Bernstein (Everett Sloane) that if he doesn’t change his habits, misfortune will consume him. Kane smugly dismisses him. And his best friend and colleague, Jedediah Leland (Joseph Cotten), cannot save him from his greed. Lessons in Citizen Kane are deep and are a reminder one must use their wealth wisely or lose more than just money.