from Tales from Pioneers and Soldiers Memorial Cemetery

By SUE HUNTER WEIR

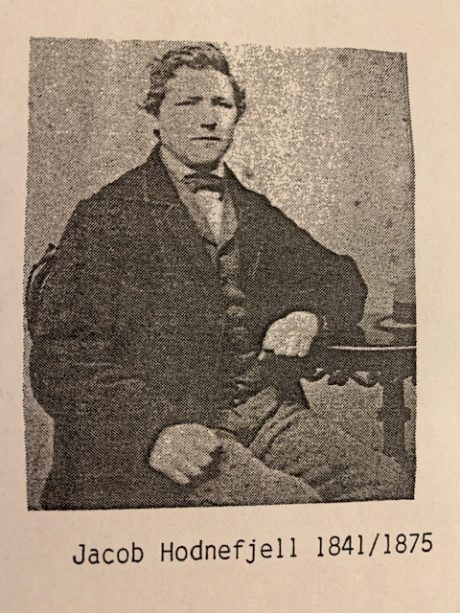

It’s been almost 150 years since Jacob Hodnefjeld died. Cemetery records have little to say about him. His burial permit notes that he was buried on November 14, 1875, but not the day that he died. His birth year was recorded as 1841 but doesn’t give a precise date and doesn’t mention where he was born. No cause of death was given.

He never married or had children but someone in his family knew his story and wrote it down. His photo and a six-paragraph biography are posted on ancestry.com. Those six paragraphs were published on page 273 of a family genealogy. As brief as it is, that biography fills in many of the gaps in Jacob’s story. It captures his hopes, his struggles, his relationship with family and friends, and offers a detailed description of the days leading up to his death.

We now know that Jacob Hodnefield was born in Hodnefield, Norway on October 30, 1841, and emigrated to the United States in 1871. He accompanied his sister Inger and her family. Inger went on to settle in Kandiyohi County but Jacob stopped briefly in St. Paul where he hoped to find work. His trunk was lost on the voyage over and was never recovered. While in St. Paul, he met B. P. Strand, a man who was later his roommate at Augsburg Seminary and who became a close friend who cared for Jacob during his final days.

Jacob couldn’t find work in St. Paul and set off on foot for Farmington, Minnesota where he hoped to find work in the harvest fields. Unable to find work as a farmhand, he worked for a railroad company.

In 1874, he enrolled at Augsburg Seminary but his academic career was short-lived. He died the following year. According to a letter that was written to Inger’s husband by Reverend B. P. Strand, Jacob “was sick for 12 days, his illness beginning with pains in chest and back and in two or three days he developed a severe hemorrhage from the nose, one hemorrhage lasting from 5 a.m. until noon.” The hemorrhaging stopped briefly but started again and “[f]rom then on, he did not look for recovery.” Strand cared for Jacob in their room until he was moved to the college’s infirmary where he was cared for by a nurse. He died on a Sunday with “Mr. Strand, Prof. Wenaas [credited with being one of the founders of Augsburg,] and another student present.”

Jacob’s brother, Johan, asked that his brother’s belongings be sold and the sale netted about $100.00 which was used to pay “his debts about the city” and his funeral expenses; the hearse and coffin cost about $18.

His college friends purchased a marker, most likely made of marble, but when family members visited his grave in 1935, they “found it crumbled” and had it removed. In 1938, sixty-three years after Jacob died, he had a new marker. And in 2024, almost one hundred and fifty years after he died, his story lives on simply because someone wrote down what they knew about him.

In her book, “Write for Your Life,” author Anna Quindlen encourages readers to write about their lives. She wrote: “Writing is the gift of your presence forever.” But, as in Jacob’s case, it isn’t just about writing about your own life. It’s about capturing the lives of others who might otherwise be forgotten. She asks: “If you could look down right now and see words on paper from anyone on earth or anyone who left it, who would that be?” It’s time to start writing before all of those stories get lost.

Sue Hunter Weir is chair of Friends of the Cemetery, an organization dedicated to preserving and maintaining Minneapolis Pioneers and Soldiers Cemetery. She has lived in Phillips for almost 50 years and loves living in such a historic community.