from the series Tales from Pioneers and Soldiers Memorial Cemetery…

Number 238 in a Series

By SUE HUNTER WEIR

This quote from the Leavenworth Daily Times sums up the life of Alonzo J. Brown, a Civil War veteran, and may be why, when his life was upended by illness, friends and colleagues came to his aid.

During the Civil War, Alonzo Brown enlisted in Company G in the 1st Kansas Infantry attaining the rank of captain. He was wounded and mustered out in 1863, but re-enlisted in the 22nd Veteran Reserve Corps where he performed light duty until the War’s end.

Although he served in those two units for five years, Brown considered himself as having performed ten years of military service. The undocumented five years most likely refer to unofficial service during an attack on his hometown Lawrence, Kansas. In 1856, William Quantrill, leader of a band of lawless Confederate raiders, attacked the town, known as an anti-slavery stronghold. They killed more than 180 men and boys and burned most of the town to the ground. Years later, in a letter that he wrote to the Senator who represented Lawrence, Brown referred to himself as one of the Boys of 56, those who had tried to defend the town during what became known as the Lawrence Massacre, the bloodiest chapter in Kansas history.

In 1857, he married Clara Ingersoll. Their first son, Alonzo Oscar Brown, died in infancy in 1858, and is buried in Kansas. Their second son, William, was born in 1861, and their third son, Frank, was born in 1867. The timeline is not clear, but Brown sent Clara and William to New Hampshire to wait out the War. It is likely that Clara was pregnant when they left since Frank was born in 1867. Clara divorced Brown for adultery in 1866.

Brown was a printer before the War. He is also believed to have been “Cosmopolite,” the anonymous author of dispatches from the 1st Kansas Infantry to the Leavenworth Daily Times.

By 1874, or perhaps earlier, he was living in Minneapolis. In July 1874, he was one of five men who incorporated the Tribune Publishing Company. He was a foreman and compositor in the newsroom for the next several years.

The first hint that there was something wrong was in 1878, when the Daily Globe reported that Brown had stepped down from his job in the newsroom and had taken over the newsstand at the Post Office “…because his health of late has been such that business of a different nature was necessary.” The Minneapolis Tribune gave a glowing tribute to his career in the pressroom, noting that he had “discharged his duties with an energy, intelligence, and faithfulness which have commanded the continued and perfect confidence and esteem of his employers.”

It was not only what the papers reported but it was also what went unsaid. Brown had a long and respected career in publishing and had numerous friends and co-workers in the trade. It is likely that his colleagues knew the nature of his health problems but were uncharacteristically tight-lipped on the subject.

According to the New England Journal of Medicine, “softening of the brain” was seen as a form of dementia caused by restricted blood flow to the brain, possibly caused by a stroke, infection, or traumatic brain injury.

He was listed twice in the 1880 Federal Census. On June 3, 1880, he was living with his mother, sister, and niece. But twelve days later, he was listed as a patient in St. Peter’s Hospital, an institution that treated the mentally ill. The papers, again uncharacteristically, made no mention of his having been committed, let alone giving a reason why.

On July 13, 1880, the Minneapolis Tribune reported that a friend had received a letter from Brown, who was “making inquiries after the post office newsstand and matters in general, and begging to be released from the asylum.” His friend reported that the letter was “purely rational.” Apparently, Brown’s wish was granted.

Friends appear to have been watching out for him and advising him about his financial affairs. On October 15, 1880, Brown traveled to Kansas and remarried Clara, ensuring that she and their sons would inherit his property. A few weeks later, on November 10th, he signed his property over to the care of a guardian which led the Tribune to announce that “Mr. Brown’s friends will rejoice with him.” His affairs were in order.

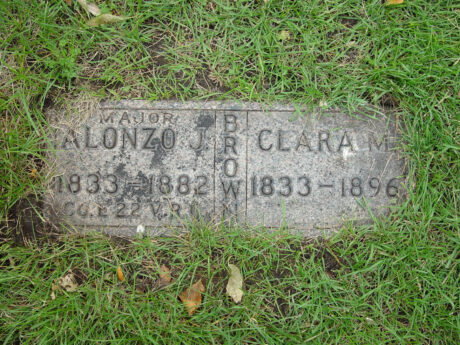

He died at home on December 11, 1882. He is buried next to his wife, Clara, and currently has two markers. One is a worn military marker, placed in 1888. The other is a marker that he shares with Clara. Although the family marker refers to him as “Major” Brown, that is not correct; his highest rank was Captain. His military marker is due to be replaced in the near future.