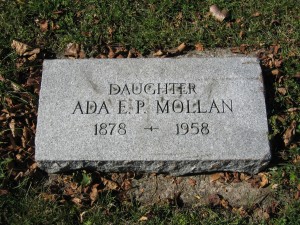

The Mollan family ran a private hospital on land now part of Matthews Park in the Seward Neighborhood. Ada Mollan, the oldest daughter, matron or proprietress, died on April 15, 1959 at the age of 79. Since the cemetery had been officially closed to future burials in the 1920s, the City Council needed to approve her burial in the family plot. Ada Mollan is buried in Lot 105, Block A with two of her nieces, her grandmother, brother, mother and one of two step-mothers.

Photo by Sue Hunter Weir

By Sue Hunter Weir

Imagine that it”'s 1905 and that someone you love is mentally ill. Medical professionals and the courts recognize that there is such a thing as mental illness but they don”'t know what to do about it. There are no medications to prescribe and talk therapy as doesn”'t exist. The only available “treatment” is confinement in a State Hospital for the Insane or, for less serious cases, a private hospital.

The Mollan family ran a private hospital at 2429 Twenty-seventh Avenue South (on land that is now part of Matthews Park in the Seward Neighborhood). In city directories, Ada Mollan, the oldest daughter, was listed as the matron or proprietress of the hospital that she and her father started sometime in the first decade of the 20th century. At various times, Ada”'s mother and two sisters worked at the hospital as nurses.

Some of their patients were “volunteers,” brought to the hospital by concerned family members. Others were sent there by the courts who had determined that the patients needed to be confined but were not ill enough to warrant being sent to one of the state”'s mental hospitals.

All seemed to go well until February 1911 when the State”'s Board of Visitors paid a visit to the hospital and declared that it was a firetrap. They called for the revocation of the hospital”'s license. The state”'s Board of Control, which had oversight over Mollan”'s and similar institutions, vigorously disagreed, as did Dennis Bow, the Alderman representing that section of the city on the city council, and Dr. Peter Holl, City Health Commissioner.

Despite the support that Ada Mollan received from a number of different sources, James Houghton, the city”'s building inspector, issued a warrant for her arrest charging her with operating an unsafe building. Specifically, he charged her for having metal screens and barred windows which would prevent patients from getting out of the building in the event of a fire. Houghton stated that he intended to have the Fire Chief and other expert witnesses from the fire department testify against Miss Mollan.

She turned herself in and her trial was set to begin on February 23, 1911. The following day the trial was postponed, and less than a week later all of the charges against her were dropped. There is no reason to believe that Houghton”'s findings weren”'t true or that his concerns weren”'t very real. The problem was that the hospital was not violating any law. He was simply a man ahead of his times.

The reason that the hospital had bars on the windows was to keep patients from escaping. And they did escape. One woman jumped out of a second story window dressed in “nothing but a night dress and a pair of stockings.” Another escaped early in the morning and “startled the neighborhood”¦by appearing in the streets very much deshabille.” She was discovered around sundown “not far from the hospital as she was strolling on a newly sprinkled lawn.” An elderly man suffering from dementia was found wandering down Hennepin Avenue. Although these patients never posed any threat to others, the same could not be said of themselves.

In October 1911 the State of Minnesota decided to no longer use Mollan”'s Hospital to house patients suffering from dementia or mental illness. No reasons were given by the local papers but officials may simply have realized that a small, family-run hospital was not up to the task of caring for, and protecting, the mentally ill. None of the other local hospitals, private or otherwise, was interested in taking them on, and they became charges of City Hospital, the city”'s charity hospital.

There is no evidence that Ada Mollan worked after 1911, but she lived for another 48 years. She died on April 15, 1959 at the age of 79. Since the cemetery had been officially closed to future burials in the 1920s, the City Council needed to approve her burial in the family plot. Ada Mollan is buried in Lot 105, Block A with two of her nieces, her grandmother, brother, mother and one of two step-mothers. Her father may (or may not) also be there, but that”'s another story.