Martin G. Farmer, Cemetery Owner, and Cemetery Sexton, We don”'t often associate cemeteries with political movements, but the connection between Minneapolis Pioneers and Soldiers Memorial Cemetery and the anti-slavery movement is undeniable. Farmers Martin and Elizabeth Layman came to Minneapolis in 1853. Like many early Minnesotans, they were born in New York and made their way west in stages””in their case, by way of Peoria County, Illinois. They bought land at what later became the corner of Cedar Avenue and Lake Street in South Minneapolis. The Laymans seem to have gotten into the cemetery business by happenstance when, soon after they arrived, a Baptist pastor asked to bury his infant son, Carlton Cressey (or Cressy), on their land.

The cemetery was founded in 1853 by Martin and Elizabeth Layman who were among the earliest members of the First Baptist Church. The Layman family”'s association with the Baptist church may explain why their privately-owned cemetery was never segregated, something that was almost unheard of it the 1850”'s and 60”'s. They opened Minneapolis Cemetery in 1858 and expanded it to ten acres in 1860. The Laymans, their farm, and the cemetery prospered, and the family built a stately house across from the cemetery gates on Cedar Street. Often known as Layman”'s Cemetery, it grew to twenty-seven acres and eventually held around 27,000 remains.

By Sue Hunter Weir

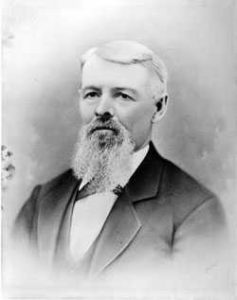

By all accounts Martin Layman, Layman Cemetery”'s (now Named Pioneer and Soldier”'s Cemetery) original owner, was a mild-mannered and courteous man. He was also highly principled. Those qualities were put to the test in 1876 in his battle with a medical student, E. S. Kelley.

Their fight was over the handling of the remains of Erick Wellson who, after three days of drinking and carousing, was murdered by one of his buddies on February 24, 1876. It was an extraordinarily grisly crime, one in which the horror did not end with this death.

Wellson”'s body was placed in the cemetery”'s vault where it remained until March 4th. On that day, Kelley went to the cemetery to claim the body; since he did not have any documentation giving him that authority, Layman refused to release it. There was something about the situation that troubled Layman and it appears that his suspicion led him to tell a lie. He wrote that: “I doubted my obligation to deliver it to him”¦ I told him [Kelley] that I was a friend to him [Wellson] and I would bury him myself.” As generous as that offer was, it”'s hard to imagine that Martin Layman, a highly religious man and a pillar of the community, counted a man with Wellson”'s reputation and habits among his friends. Most likely Layman told a fib in order to ensure that Wellson”'s remains received a respectable burial.

Kelley returned with a certificate from a local undertaker who did have a legitimate claim to the body. Layman recognized the need to have complete information about the condition of the body for the upcoming murder trial and agreed to turn the body over to be examined on condition that it would be returned to him in as close to its original condition as possible.

Eventually some, though not all, of Wellson”'s remains were returned to the cemetery. On opening the coffin, Layman was horrified to find Wellson”'s organs and tissue but no skeleton in the box. He also found the bodies of two cats. It was, according to Layman, “skillful butchery.”

On March 9th, Layman wrote a letter to the Minneapolis Tribune in which he explained what he believed had happened and when. He described himself, as the Cemetery”'s Sexton, “most grossly and maliciously insulted.”

Three days later, Kelley responded to what he referred to as Layman”'s “long, uncalled-for vindictive article.” He wrote: “I am surprised! Shocked! To think of the outrageous manner in which he has attacked me.” Although he offered no proof, Kelley accused Layman of conspiring with the County Coroner to profit from the sale of bodies to favored physician-clients. Kelley admitted, in a remarkably understated line, that “In boxing the remains we were not so particular, perhaps as we ought to have been”¦” He claimed that was the case because he had expected to re-open the coffin to replace Wellson”'s skeleton and remove the “nuisance” from the coffin, a claim that was denied by the physician who was supervising Kelley”'s medical training.

Two days later Layman had his last say on the matter. He wrote a letter containing a blistering personal insult. Kelley had challenged Layman to “arise and explain” the disposition of another man”'s remains to which Layman replied “”¦had you one more idea running in that anatomical strata of your cranium, you would never ask me to ”˜arise and explain.”'”

The battle between the two men appears to have run out of steam at that point. Mr. Wellson”'s body was interred in the cemetery”'s paupers”' section. E. S. Kelley did become a physician; he died during the influenza epidemic in 1919 and is buried in Lakewood. Martin Layman died on July 25, 1886 and is buried in Crystal Lake Cemetery.