By JESSIE MERRIAM, Public History student working on a mobile museum for Our Streets Minneapolis.

Originally published in local punk-adjacent newsletter zine, Restless Legs Inquirer. Re-printed with permission.

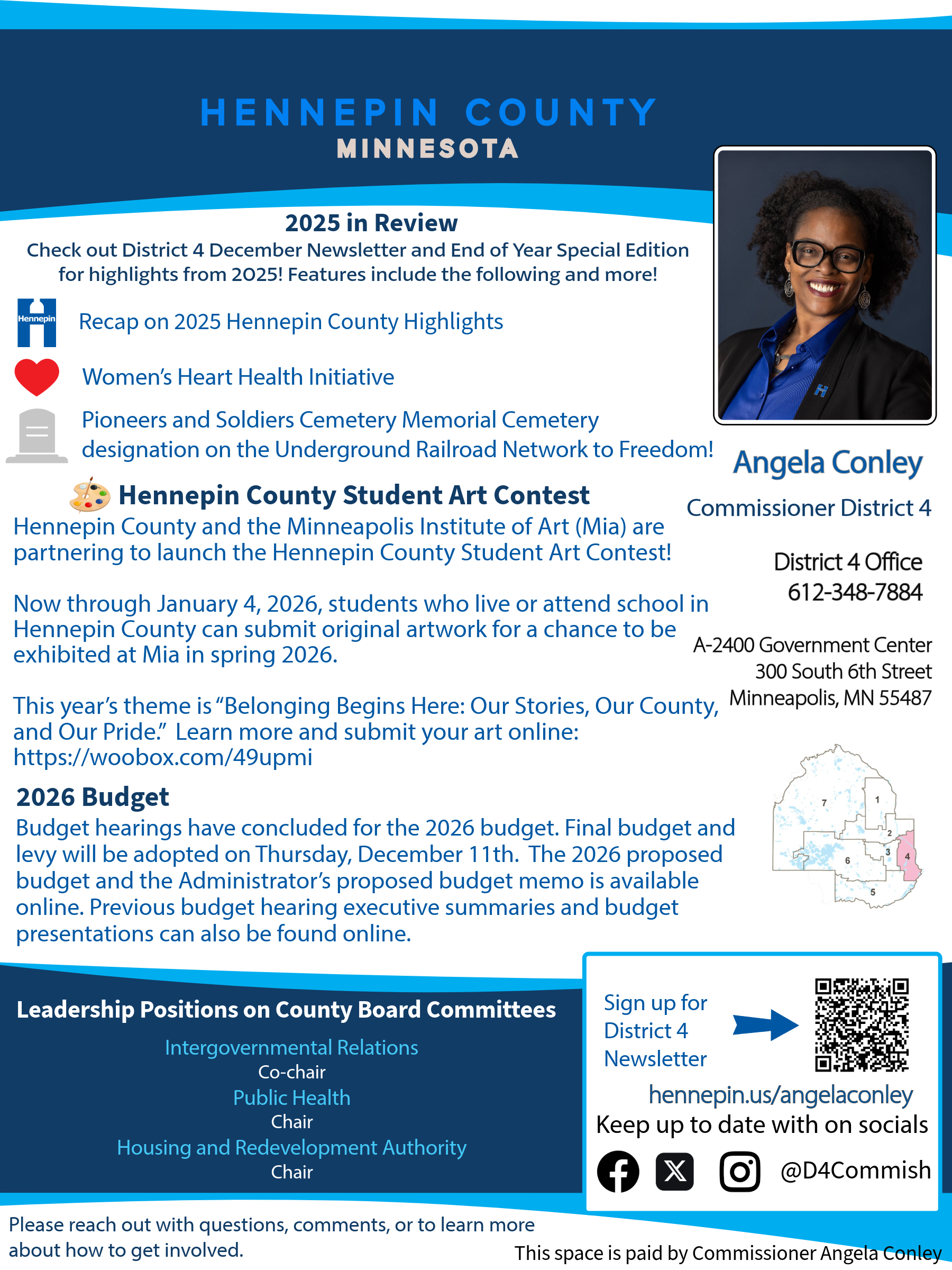

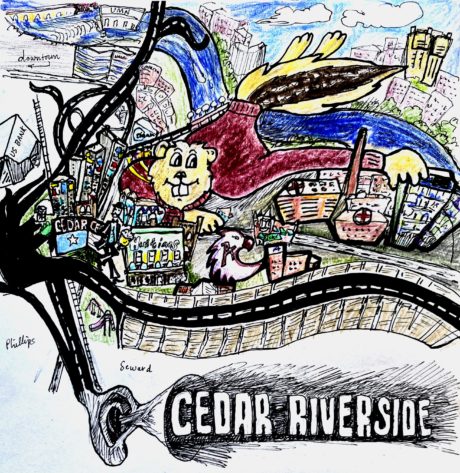

The wavy-crusted pie slice that is now called Cedar Riverside was once a continuous neighborhood with Seward and Phillips. Also known over the years as Riverside, Seven Corners, Bohemian Flats, Snoose Boulevard (Snus = Swedish snuff), “The Haight Ashbury of the Midwest,” and “Little Mogadishu,” Cedar Riverside has always been a place of intersections. “There were no neighborhoods before Urban Renewal–we lived in South Minneapolis! They needed clever labels. Our speech had nothing to do with neighborhoods,” reported a Seward neighborhood elder historian over coffee this January. “Block groups! That’s the basic foundation–come on now! Organizing neighbors to support each other in small groups.”

MANY GROUPS HAVE SHAPED THE CHARACTER OF CEDAR-RIVERSIDE:

1805: A small group negotiates “Pike’s Purchase” that will displace the Dakota from their pathways between the two falls, Owamniyamni and Minnehaha.

1920: The city’s first Black congregation, St. James AME, moves to an old synagogue on 15th Ave (demolished for I-35).

1956: The Federal Highway Act funds the interstate system, and the University of Minnesota is granted eminent domain by the legislature. Both buy up affordable property in Riverside for construction.

1965: A man and a woman hover over a utopian model of high rises, a “New Town in Town” (only Riverside Plaza was built).

1968: A group of activists take over an old chapel, helping suburban teens and locals with medical needs, drug issues, vet needs, and a free pantry too (the People’s Center continues today).

1970s and 80s: First Vietnamese, then Somali find community in Cedar Riverside (in 2021, 5.5% of Cedar Riverside residents spoke Oromo, and 37.5% spoke Somali).

A 1934 WPA survey declared “the Riverside area one of the most dilapidated” neighborhoods in Minneapolis noting its “great number of houses located on back lots..overcrowding, the number of outhouses, and the number of absentee landlords.” Typical of the time, the lack of opportunity for homeownership, home loans, or home improvement were seen as the fault of the laboring class.

In the 1920s and 30s residents of Bohemian flats fought unknown landlords for their squatters rights in the shanties along the Mississippi flood plains, until they were evicted through eminent domain for the city’s coal barge yard in the 1930s.

“There are all kinds down here; and we are not so very poor either, though some of them are. O yes, we have awfully much fun, a dance or a concert every two weeks…The boys move all the things in one room, and we dance in the other.”

The furnishings of this cottage were the same as is found in the small country farm houses all over the land…there is more real family life in these homes than in many more pretentious ones.

“Aren’t you afraid of the rising river?” was asked. “O no, the city try to frighten us, but it is never very bad.”

From “One View of Life,” Minneapolis Tribune, March 21, 1897

Some institutional and business leaders were not fond of the thriving bar scene, especially as the University saw the district as a threat to respectability. “There are narcotics users, prostitutes and homosexuals in the area” (Minnesota Daily, 1961). “The neighborhood is racially mixed, with Negroes, Indians and whites living side by side. They are lower income groups, containing many transients and many elderly pensioners” (Minneapolis Morning Tribune, 1964).

Even as the area was targeted for disinvestment and gentrification, the neighborhood persisted as a home to vibrant community–walkable groceries, barbershops, pharmacies, Pillsbury House, Seven Corners Library, scores of ethnically diverse churches that also functioned as community ed and rec centers, and bars and nightlife that were more inclusive than many mid-century Minneapolis neighborhoods.

“It wasn’t a real spiffy neighborhood and it was mixed,” Gloria Olson recalled in her interview for the Lesbian Elders Oral History Project (MNHS). The Holland Bar, for example, where the Red Sea is now, “it was like a cross between a gay bar and a neighborhood bar” in the 1950s and 60s, across the street from a fried chicken spot owned by a Black queer woman.

“The thing is, the Extemp was more than just a coffeehouse. Downstairs it had a little restaurant area and performance space …There were chess players, talkers, hippies, beatniks, do-gooders and just plain old hangers-on. And then there were the musicians….”- Dakota Dave Hull

“When they were tearing down houses & well into building the freeway [in the 1960s] we were mighty incensed. One night after closing the 400 we went to take a look at the progress/ destruction. We started asking what the ‘‘Monkee Wrench Gang’ would do – when we found a D12 Cat dozer, Ralph climbed into the driver’s seat saying ‘I used to drive one of these on the kibbutz in Israel. Whoa, lookit that, the key’s in the ignition!’ That was a wild ride – pushed around a lot of dirt blocking other equipment. Meant nothing but it sure felt good.” – New Riverside Café employee, 2023

Hear more stories/share more stories:

Write to Jessie at jessie@ourstreetsmpls.org

Check out the Cedar Riverside

mobile museum at Open Streets Cedar

on August 20, 11am-5pm

On July 17, MNDOT released its 10 potential project proposals for the Rethinking I-94 project that includes the Cedar-Riverside corridor. Share your thoughts and read more with this survey:

https://talk.dot.state.mn.us/rethinking-i94/survey_tools/rethinking-i-94-alternatives-survey