BY LAURA WATERMAN WITTSTOCK

My writer”'s instinct reacted to the metaphor, “reframing Minnesota,” as a failure to see the content within the frame. So I decided to follow that, by beginning with a hard look at the large painting that sat in the Minnesota governor”'s reception area. It is the source of controversy about whether the painting should remain in the state Capitol, once the extensive renovations underway now are completed. It is seven feet four inches by ten feet ten inches wide. In this painting, government officials are on a raised platform and Native people are sitting submissively on the ground. It is a grand view of the signing of the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux (1851), and of the painting, the Minnesota Historical Society describes the Native people as being dressed in “barbarian finery.”

In another painting of the same size we see Father Hennepin depicted standing with a great gesture while seemingly submissive Native people sit piously below the priest with arms outstretched toward the falls. Were they giving up the falls so willingly? Was the island in the falls, center of Dakota spirituality, such an easy place to leave? Both of these paintings were installed in 1905. So what was happening in 1905 in Minnesota?

Native people were not citizens of the United States. The 1862 Dakota War still left stinging anger in the immigrant communities, and the Dakota patriot felled in the war, His Red Nation (Little Crow,) suffered the further indignity of having his head removed and his skull placed at the Minnesota Historical Society. It was still there in 1905 and was there until repatriated in 1971. The 1862 War resulted in the largest public execution in the country”'s history. Were it not for presidential pardons by Abraham Lincoln, 304 would have been executed after the five-minute judgments by the Henry Sibley kangaroo tribunal. Military rules of conduct coming into use in the United States would have protected these foreign military prisoners, who were patriots and protectors of their lands and sovereignty, but Sibley chose to treat them as common criminals. The greed for land was far greater than any regard for human life, so much so, that Governor Alexander Ramsey said all Dakota “must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the state.” The thinly veiled greed for land needed no cover up. By 1905 any pangs of regret were smothered by a sense of victory over adversity and even misbegotten patriotism.

The Native population was being overrun in 1905 by the numbers of immigrants who were invited by the state to come and live on Native lands. The savage cutting of Minnesota”'s old growth trees was so efficient that 90% of the original forests would be gone. This treasure shrank to the tiny Chippewa Forest, saved by president Theodore Roosevelt, who famously had said before that the one thought he had when contemplating a tree was to cut it down. During the winter of 1898, just seven years before 1905, federal government officials and a host of other interests argued the question of what to do with the lands, the forest, and the “Indians” in northern Minnesota. All three were in the argument as if all three were of equal or similar concern. The hubris of the United States and its representatives clearly showed the disregard for humanity it held, even to the point of wanton killing and starvation. In its never-ending land greed, the federal government trampled on its own most solemnly entered into treaties.

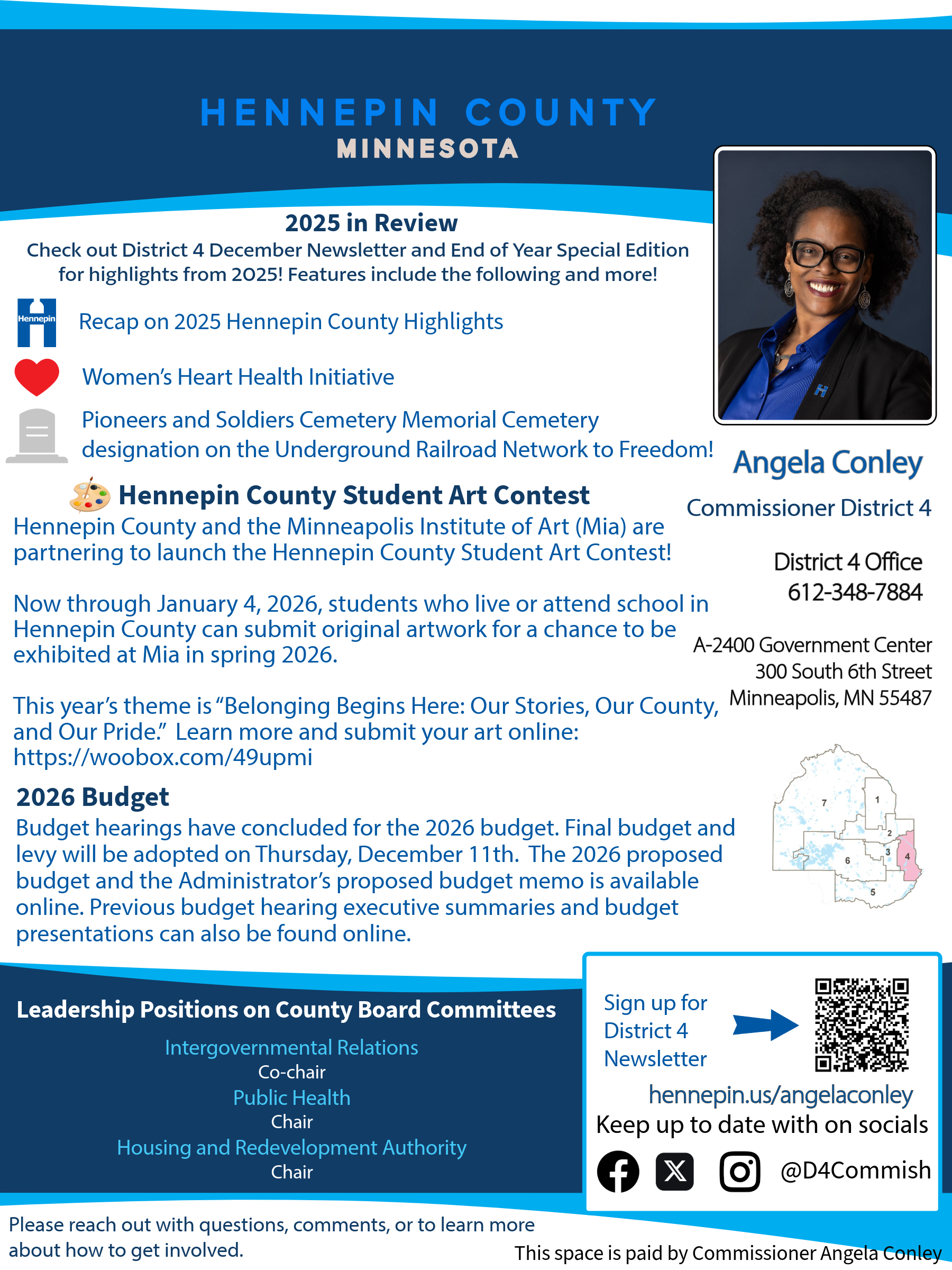

- Minnesota State Seal 1858 to 1971

- Current Minnesota State Seal

There is more, but it is clear that when the paintings went up in the state Capitol, Native people were considered subjugated, exterminated, and pacified. That attitude is frozen in the images visitors see when visiting the Governor”'s reception area today. There are no images that truthfully tell the story of immigrant/Native relations: the forced starvation of Little Crow”'s people, the peaceful relations of the two peoples when the Dakota adhered to the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux, while the government left them to starve, the long, hard history of the Dakota peoples who were repeatedly betrayed by the British in 1753, the French in the same time period, the Americans in 1812, and the British again as they left the area and all promises to the Dakota behind. By 1862, the Americans swooped in on the weakened Native Nations, to grab lands for food. What hungry hordes these must have been from Europe that regard for human life was cast aside. That legacy lives on today and cannot be erased simply by time.

So the question remains of how to forgive the betrayal and perhaps even give some new meaning to the paintings that hung in Minnesota”'s state Capitol. Something like Picasso”'s “Guernica” comes to mind, as an alternative view of that balmy day in 1851 should like when after the treaty was signed. The painting by Picasso shows the bombing of a Basque town in Spain, and the destruction of all life. In contrast, the game the Dakota people relied on were relentlessly killed by the settlers and starvation set in. There are such paintings, done by Native artists, and new art could be commissioned.

We are a moment in history when Minnesota could take a bold step to correct its historical view of its own bloody past. But it would seem that the pain of reality is too great to view with open eyes. Were we to do that, we would have to take a good look at Minnesota”'s state seal. In the original, as with today”'s seal, we see the stump of a tree, evidence of the cutting of millions of trees. The trees made way for the plowman who took the prized land. And in both seals, we still see the Native, riding away into the west, just as Governor Ramsey promised to drive “them forever beyond the borders of the state.”

No matter how much the official language concerning the seal tortures the meaning of the image we all see, there can be no doubt that the 1858 view of Native people is the same view we see today. The Native is riding away.