Historians collecting stories from people who lived in path of I-35W in South Minneapolis

TESHA M. CHRISTENSEN

Historians Denise Pike (far left) and Greg Donofrio (far right) of the University of Minnesota lead a walking tour of Interstate 35W, traveling on both sides of the freeway to talk about how the interstate cut through a neighborhood. They are working to collect stories of people displaced by the interstate construction. Email donofrio@umn.edu or pikex063@umn.edu. Public meeting on history set for Oct. 10 at Hope Community.

by Tesha M. Christensen

Does Minneapolis have its own Rondo?

Some believe that the more they dig into how Interstate 35W was planned and built through South Minneapolis that they will discover a missing neighborhood, similar to the one destroyed when Interstate 94 cut through St. Paul”™s Rondo neighborhood.

“This is our Rondo,” said Shawn Lewis who grew up in South Minneapolis. “We just don”™t know it yet.”

The questions come as Interstate 35 undergoes major construction once again in South Minneapolis. What it was like when the freeway was first built in the 1960s and how did it affect the lives of the people who lived in its path?

Thus far researchers with the University of Minnesota have delved into the historical record, scouring newspapers and Department of Transportation records at the Minnesota Historical Society. Next, they are looking for stories from the people who were directly affected by construction of I35W in South Minneapolis. Email Greg Donofrio at donofrio@umn.edu or Denise Pike at pikex063@umn.edu.Â

Residents can also connect during a Public History of 35W event on Thursday, Oct. 10, 6-8 p.m., at Hope Community-Children”™s Village Center (611 E. Franklin Ave.)

“The only way we can make this a community-based project is with the community,” observed Donofrio.Â

WALKING TOUR WITH SIGHTS AND SOUNDS OF CONSTRUCTION

A walking tour on Saturday, Sept. 7 led about 30 people through one section of the construction area to give them perspective into the noise and dust generated during a road project of this magnitude.

A walking tour on Saturday, Sept. 7 led about 30 people through one section of the construction area to give them perspective into the noise and dust generated during a road project of this magnitude.

Organized through the Hennepin History Museum, the walk was led by historians Denise Pike and Greg Donofrio, with help from Aaron Tag of the Minnesota Department of Transportation.

Pike pointed out that most of what people experience of the freeway is driving down it.Â

But how was it planned? How was it built? How were communities affected by it then and how are they affected now?

The tour began at the Hennepin History Museum at 2303 3rd Ave. S. in Minneapolis, headed north to the Franklin Bridge, walked along the east side of the freeway down S. 5th Ave., crossed the interstate again on the 26th bridge, and ended back at the museum.

Freeways answer to urban crisis

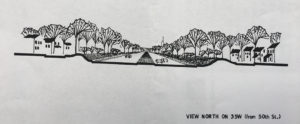

Minnesota Historical Society, MN Department of Transportation collectioN

This original sketch was presented to the public showing what the freeway would look like in South Minneapolis.

At the Franklin bridge, participants viewed the 35W construction at 94 and learned about the transportation needs of the late 1950s and 1960s, and how freeway planners designed the I-35W freeway.

The federal government agreed to pay for 90% of freeway construction with the states left with just 10% of the total bill. Between 1956 and the early 1970s, over 42,000 miles of freeway were constructed in America. An estimated 62,000 housing units were destroyed and about 200,000 people displaced annually, observed Donofrio, who works as the director of the Master”™s of Science in Architecture, Heritage Conservation and Preservation graduate program at the University of Minnesota.

The freeways were an answer to the Urban Crisis facing cities in America after many white people flocked to the suburbs after World War 2. “The cities sought to remake themselves,” observed Donofrio. “The freeways seemed like an urgent thing to build.”

There was pressure to build them as quickly as possible.Â

Minnesota Historical Society, MN Department of Transportation collectioN

”˜Some call they didn”™t know the freeway was being constructed until they heard the bulldozers,” said Denise Pike of the University of Minnesota.

Back then, the Department of Transportation held one public meeting on the proposed freeway project, pointed out Pike, and it was one early in the process. In 1968, federal policy changed to require two public hearings. Today, things are very different, pointed out Tag, who observed that today the public is engaged prior to the start of design, in the middle and at the end. With the current project, two pieces of property were displaced to provide access onto Lake St.

Researchers haven”™t found much yet about what the planners presented, but there is an original sketch showing a lovely tree-line stretch of roadway with two lanes in either direction. There isn”™t much record of opposition to the freeway, either, said Pike, although they dug up a petition sent to the Governor that was signed by 600 South Minneapolis residents concerned that they were being paid market value not replacement value.

There were no real unified neighborhood groups in this part of South Minneapolis at the time, and they have not found any groups that opposed the freeway coming through this particular section.

When the freeway was expanded because it had already reached capacity in 20 years, there is a record of more resistance by community members.

”˜When they heard the bulldozers”™

Property acquisition for the interstate began in 1956, but construction didn”™t start until the early 1960s.Â

“Some recall they didn”™t know the freeway was being constructed until they heard the bulldozers,” said Pike.

The path of the freeway cut an unnatural swatch through South Minneapolis, and residents weren”™t happy with the distance created by the interstate. People of color also payed a higher cost in the amount of air pollution and the health effects it caused.Â

“In order to reconnect their neighborhood, the community came together, devised a plan, and lobbied tirelessly,” according to an article from the Alley in March 2011. “Their persistence finally paid off in 1971 when the city agreed to install a pedestrian bridge and again in 1974 when the sound barrier walls were built.”

The pedestrian bridge at 24th is currently being reconstructed. The new one will be 20 feet lower than the old one and wider, and will connect a bit further south.

TESHA M. CHRISTENSEN

The pedestrian bridge at 24th is being reconstructed. The original one was built following a push by residents to reconnect the two sides of the freeway in the 1970s. They also pushed for sound barriers to help ease the noise and air pollution.

BLACK RESIDENTS AFFECTED MORE

Why does the freeway jog like it does in South Minneapolis and not meet up with the stub at Lyndale/MN 121 and 62? Pike pointed out, that if it went straight it would have gone right through the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and disturbed the grand residences around it. So instead, it was pushed to the east where a higher percentage of black residents lived. The divide has grown over the years. The Whittier neighborhood has 56% white and 43% people of color, while Phillips has 18% white and 81% people of color.

Many of the pieces of property purchased for the project were not occupied and used by the owners, but were rented apartments and business spaces. Renters were not compensated nor did they receive help with the costs of moving.Â

“Tenants got nothing,” said Pike. “This affected people of color more heavily.”

An article from the Minneapolis Morning Tribune on Feb. 13, 1964 quotes a family concerned “that their race limits their choice and presents other problems.”Â

The difficulty people of color had purchasing homes and living in certain parts of Minneapolis is being studied by the Mapping Prejudice project through the University of Minnesota. Through a combination of writing directly in the deed that a person of color couldn”™t buy a piece of property and mortgage red-lining certain areas, people of color were limited in their options.

Shawn Lewis is now a member of the Northside Environmental Justice Coordinating Council, but grew up and attended Minneapolis Central High. “We know the story of Rondo and how that black community was split,” stated Lewis. “I”™ve felt there”™s a story in South Minneapolis. I think we”™re in the beginning stages of trying to surface that story.”

He added, “They took out so many houses. What happened to all the people who were affected?”

Lewis remembers his mother telling him how upset people were about Interstate 35W, and how the gap in the neighborhood stood there for a long time before the roadway was constructed.Â

He also recalls a professor talking about urban renewal. “”˜That wasn”™t urban renewal – that was Negro removal,”™ he”™d say,” said Lewis.

He”™s glad that people are trying to raise awareness about the impact of building freeways.

Were you displaced by the construction of I35 in South Minneapolis?

Researchers Greg and Denise Pike would like to talk to people about their experiences. Email donofrio@umn.edu or pikex063@umn.edu

A Public History of 35W

Ӣ Hosted by the Minnesota Department of Transportation and Hennepin History Museum

Ӣ Thursday, October 10, 6-8 p.m.

Ӣ Hope Community-ChildrenӪs Village Center (611 E. Franklin Ave.)

Owning Up: Racism and Housing in Minneapolis

Since the 1950s, Minneapolis has envisioned itself as a “model metropolis.” The city is lauded for offering the right mix of amenities and affordability. Boosters brag about the parks, lakes, efficient government, and the city”™s vibrant arts scene. They are adamant that their city, as the New York Times once observed, has “all of the answers.”

However, this myth hides an uncomfortable reality. Minnesota has some of the highest racial disparities in the United States. People of color in Minneapolis are more likely than white residents to live in poverty, experience violence, and suffer chronic illness. They are less likely to graduate from high school or own their own home. We believe housing is the foundation of these disparities.

Owning Up explores the history racial housing discrimination in Minneapolis through the stories of three black families. Their experiences are displayed alongside the policy decisions and social practices that institutionalized racial segregation and continue to shape the city of Minneapolis. While the passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act made policies like racial covenants and redlining illegal, they did not solve racial segregation.

>> View the permanent Owning Up exhibit, Sabathani Community Center (310 E 38th St.).