Following is a segment of Chapter 12 of a book entitled: Wendell Phillips, Social Justice, and the Power of the PastÂ

Edited by A. J. Aiséirthe and Donald Yacovone, Louisiana State University Press, 2016Â

This book is the 20th book of the Series:Â ANTISLAVERY, ABOLITION, AND THEÂ ATLANTIC WORLD,Â

R. J. M. Blackett and James Brewer Stewart,Â

Series EditorsÂ

EXCERPT FROM CHAPTER 12:

“The Phillips Community of Minneapolis: Historical Memory and the Quest for Social Justice”:

Pages 339-344

By David Moore, Harvey M. Winje, and Susan Gust

in consultation with James Brewer StewartÂ

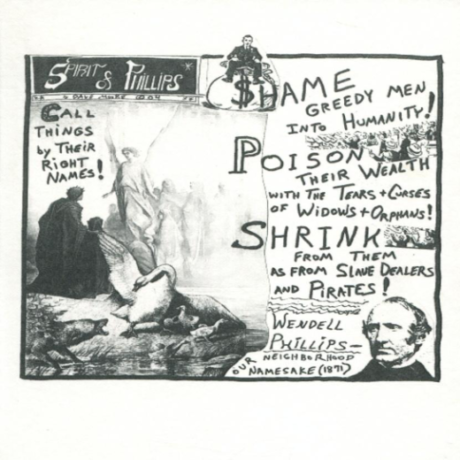

For close to two decades, from 1987 through 2005, our community followed this Wendell Phillips exhortation when uniting in unprecedented solidarity to address the mounting injustices posed by those who tried to dictate the terms of our physical environment. Throughout these particular struggles, we surely did “Call Things by Their Right Names”. The descriptor that best captured what we were up against was “environmental racism.” Thanks to twelve years of uninterrupted protest, conducting our own research and garnering the attention of the media because of our creative techniques, we finally achieved a clear-cut environmental victory, not only for the neighborhood, but for the entire city. But none of this would come to pass until, as Phillips advised us, we had done everything possible to “shame greedy men into humanity.”

In 1987, the Hennepin County Board, the duly appointed manager of waste for Minnesota”™s most populated county, attempted to saddle us with a 10-acre trash and garbage transfer station. Over 10 million dollars had been appropriated by the County Commissioners for this development. Their plan was to consolidate and transport waste from every part of Minneapolis using city compactor garbage trucks making approximately 750 truck trips per day to the proposed garbage transfer facility. From there, the garbage would be transferred to semi-trailer trucks and delivered to the County”™s existing garbage incinerator located in downtown Minneapolis. When thirty-five houses and eight businesses were summarily demolished by the forced eminent domain, the community rose, unified by our deep indignation and driven by the imperative to resist. We forced the City to hold widely-publicized (and frequently raucous) open hearings before the Zoning Board. We all came together to battle for the future of our children, not simply to score a victory over oppressors who held political power. Our children surely deserved better than a garbage transfer station in their backyard, we insisted. They most certainly deserved better than an endless succession of rank-smelling garbage trucks rumbling though our streets, generating constant noise and emitting clouds of choking exhaust. Thus began twelve years of uninterrupted agitation, protest, politicking and remarkably ingenious problem-solving throughout which our community sustained unbreakable unity. Wendell Phillips, we are certain, would have applauded.

For the first time in the history of the Phillips community, homeowners and renters joined in a common cause. We also coalesced into a truly multicultural protest movement with people from every ethnic group “blending with one another like the colors on a pigeon”™s neck” (this simile was a Wendell Phillips favorite.) Native Americans, many of them women, played a prominent role as front-line resisters Little Earth of the United Tribes of Minnesota (discussed in detail below), the nation”™s largest American Indian public housing complex, sat three blocks from the transfer station”™s proposed location. We forced the authorities to hold the public hearings required for the permitting process in the Little Earth gymnasium. At the meetings themselves small Native children waved hand-lettered signs and banners they had made featuring sayings such as: “We may be poor but we are not stupid”; “We are worth more than garbage.” Mothers and grandmothers who had never before attended or spoken in public testified forcefully while condemning the health effects and related dangers being proposed for them and their children. What deeper motives were driving those in authority, these women queried, when they grievously threatened the children of our nation”™s First People.

For more than a decade, the combined impact of incessant protesting, media attention and political arm-twisting kept the transfer station at bay. The conflict turned decisively in our favor, however, once we proposed a solution to the waste management problem that was simply too intelligent and practical for the “those with authority” to turn down.

After analyzing the same statistics and technical information cited by the “experts” in defense of the transfer station, as well as garbage truck routes and recycling statistics we were able to prove definitively that Hennepin County”™s current recycling efforts made the proposed project completely unnecessary. Instead of wasting 10 million dollars, Hennepin County could, at minimal cost, position itself as a national leader in the “greening” of American cities- and the people of Phillips showed them how to do it. Our initial struggles against the transfer station had required several of us to immerse ourselves in the theories and practices of developing a “green economy” and the realities of environmental racism. We sought additional knowledge and advice from experts in other environmentally distressed, racially polarized cities such as Los Angeles. We learned, much to our delight, that there was actually “gold in the garbage.” Around 33 percent of the solid waste stream in Minneapolis was made up of construction materials, much of it reusable. Instead of paying to get rid of refuse, we could be generating serious income!

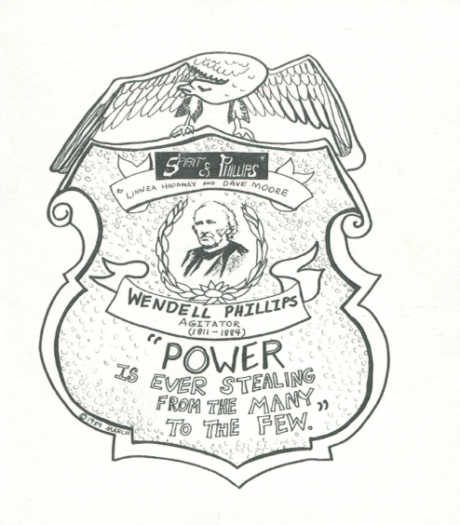

Thus was born the Green Institute, which in 1995 opened The Re-Use Center, a 26,000 square foot facility set in a low end, 1950”™s-style shopping center located at one of the key commercial edges of Phillips community. The enterprise brought many befits to our community that went far beyond generating profits from discarded building materials. The Reuse-Center created jobs for about a dozen local residents, offered home improvement classes, conducted environmental education workshops for local elementary schools and, closely mimicking the organization of a Home Depot store, sold an amazing range and quantity of recycled building materials. In all these creative endeavors, as Wendell Phillips might well have pointed out, power itself was now being recycled from “the few” who had attempted to victimize our community back into the hands of “the many” where it surely belongs and where , as the citizens of Phillips have shown, it does the most good.Â

Had the people of Phillips achieved environmental justice? Not yet. A few years after our battle against the transfer station, we learned in 2003 of a soil sample study demonstrating that our neighborhood was awash in arsenic poison emanating from an abandoned industrial site. The neighborhood promptly labeled the site “Arsenic Triangle” which describes the geometry of its borders. Right away The Alley opened an all-out campaign to educate its readers and to mobilize them around demands that “the powers that be” deliver effective solutions. Wendell Phillips captured perfectly our journalistic motivations when reflecting on his own distinguished career: “We came into the world to give truth a little jog onward and help our neighbors”™ rights” (We display this quotation on our newspaper”™s masthead.)

Buoyed by this historical connection we filled The Alley with a volley of in-depth pieces explaining the problem and spotlighting the government agencies responsible for solving it. Between January 2005 and November 2007 we published nine articles about arsenic contamination that demanded action by “those in charge.” We publicized each and every community meeting of which there were dozens, printed letters from community members expressing anger and concern, and composed pungent editorials criticizing government bureaucrats for inadequate responses. All the while we kept fully in mind the fact that in 1852 Wendell Phillips had delivered a compelling speech, titled Public Opinion, in which he stressed that agitators who expose corruption and denounce its practitioners are, in truth, democracy”™s most vital defenders. Our actions throughout the struggle to clean up “Arsenic Triangle” gave substance to his thoughts.

The resolution of this crisis confirmed the truth of Phillips”™s insight concerning public opinion. A passionate community activist and parent H. Lynn Adelsman, researched and laid out the problem with such exceptional clarity that neighborhoods beyond the borders of Phillips suddenly realized that our cause was also theirs. Meantime, our deeply engaged State Representative, Karen Clark, pushed for the intervention of higher levels of government with the result that in 2007 a broad area surrounding “Arsenic Triangle” was declared a federal Superfund project. Two years later, the Environmental Protection Agency had appropriated up to $25 million to remediate and restore not only the site, but also approximately 500 arsenic-affected residential properties. Lawns were excavated to a depth of 12 inches, gardens to a level of 18 inches. The “Triangle” itself was completely decontaminated.

The work on the arsenic issue followed a 10-year collaboration to reduce childhood lead poisoning in Phillips. Partners included five University of Minnesota medical and science departments, the Minneapolis and Minnesota Health Departments, the office of our State Representative Karen Clark, the Sustainable Resources Center, and the Honeywell Foundation The results of these combined efforts led to two federally-funded multi-million dollar, community governed research grants based on the expectation of designing improved intervention programs. The research was co-conducted with community members employed at living wages as peer educators, data entry specialists and translators. Though we did not know it at the time, we had designed a Community-Based Participatory Research Model of shared power, and decision making that worked to the benefit of all involved. All information and analysis developed through this research needed first to be shared with the community before being published in specialized academic journals. As a consequence, in 2000, community residents and academic researchers co-produced a12-page insert in The Alley Newspaper that summarized for everyone what our research had revealed about the threats of lead poisoning and how best to combat them. Exactly as Wendell Phillip had recommended we were choosing to “Call Things BY Their Right Names.”